Like most stars in the Milky Way, our Sun was born in a cluster of hundreds of new stars in a cloud of glowing gas and dust like the Orion Nebula, then settled down with its siblings in an open star cluster like the Pleiades. Over the next few hundred million years, as it made its way around the Milky Way, this new cluster of stars was slowly pulled apart by tidal forces and the gravitation pull of passing dust clouds. Some of the family members may have traveled together for another billion years as a stellar association or a moving group. But like human siblings, they were eventually separated once and for all by the vicissitudes of the outside world.

After 5 billion years, the Sun has made some twenty full turns around the Milky Way, so you might expect that all of its siblings have been dispersed and blended into the galaxy and impossible to identify. But astronomers are a clever lot, and a study announced in 2014 postulated that the 6th-magnitude star HD 162826 may in face be a long-lost sibling of our Sun. It’s about 15% more massive than our Sun, about twice as intrinsically bright, a little hotter, and has a similar chemical composition. The star lies about 100 light years away in the constellation Hercules; you can see it easily for yourself with binoculars or a small telescope.

How is it possible to identify a star that formed from the same gas and dust as the Sun more than 5 billion years ago?

The simple answer is chemistry and motion. The astronomers compared the detailed optical spectrum of 30 candidate stars to look for a family resemblance in terms of chemical composition. A solar sibling with a similar mass to our Sun should have the same elements in its atmosphere because it formed from the same cloud of gas and dust. The spectrum of HD 162826 and the Sun match closely, especially the rare chemical elements barium and yttrium.

The team also measured the historical motion of HD 162826. It seems the star mingled with our Sun at a distance of just 30 light years about 4 billion years ago, exactly as expected for stars once loosely bound in an open cluster.

These measurements don’t prove that HD 162826 is a solar sibling, and a subsequent study argued it is not. But the star has the right credentials. As more stars are surveyed, it may be possible to find more potential siblings and trace their motion back to the birthplace of our solar system. Astronomers once suspected a sun-like star in the constellation Pavo, HD 186302, might have originated in the Sun’s birth cloud, but subsequent calculations of its orbit around the Milky Way suggest it did not. The search continues.

Does HD 162826 have planets? Since it has a similar composition to the Sun, it may have formed in a dusty and rocky cocoon cloud formed planets. In a sense, these planets would be “cousins” of Earth and other planets in our solar system. So far, there’s no sign of planetary bodies of any kind near this star, at least in surveys for close-in Jupiter-sized planets. There’s been no search yet for Earth-sized bodies around HD 162826.

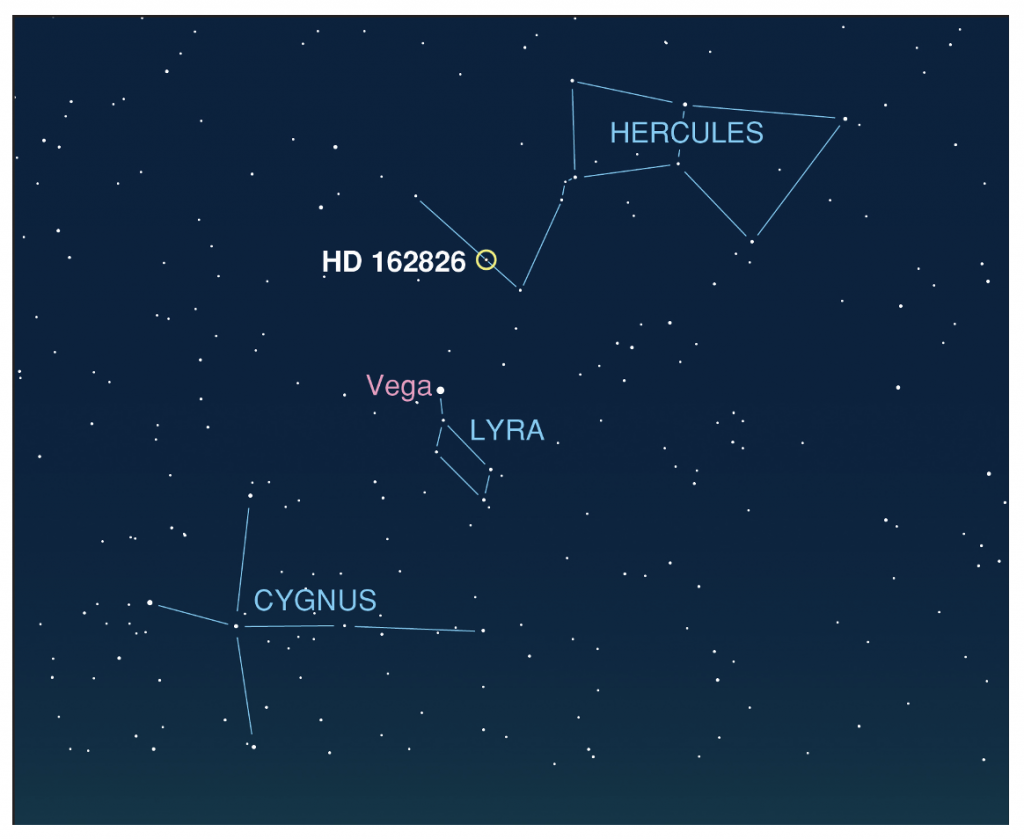

If you’re keen to see HD 162826 for yourself, it’s an easy sight with binoculars. The star lies in the upraised “club” of the constellation Hercules just northeast of the famous “Keystone”. It lies on a line about 1/3 of the way from θ (theta) Herculi to ι (iota) Herculi (see image above).

There are three stars located in the area shown in the above map. The image below shows which is HD 162826. At magnitude 6.5, the star is just beyond the limit of naked-eye detection, but it pops out nicely with the slightest optical aid.

Of course, hundreds or even thousands more stars formed together with the Sun. Some were immense blue supergiant stars that burned their fuel quickly and blew up as supernovae well before the Earth had a chance to congeal into a planet. Others – perhaps most of them – formed as small red dwarf stars that will continue to burn long after the Sun expires. And all the while, the galaxy churns out new star clusters formed from primordial hydrogen and helium and scattered heavy elements cast off by old stars in a perpetual cycle of stellar life and death in the Milky Way.

Share This: