Solar observers haven’t had much to see on and around the Sun in the past several years. But that’s starting to change as our home star begins to show signs of activity in the form of increasing sunspot numbers and other dynamic features as a new solar cycle – number 25 – gets underway.

So, what’s a solar cycle?

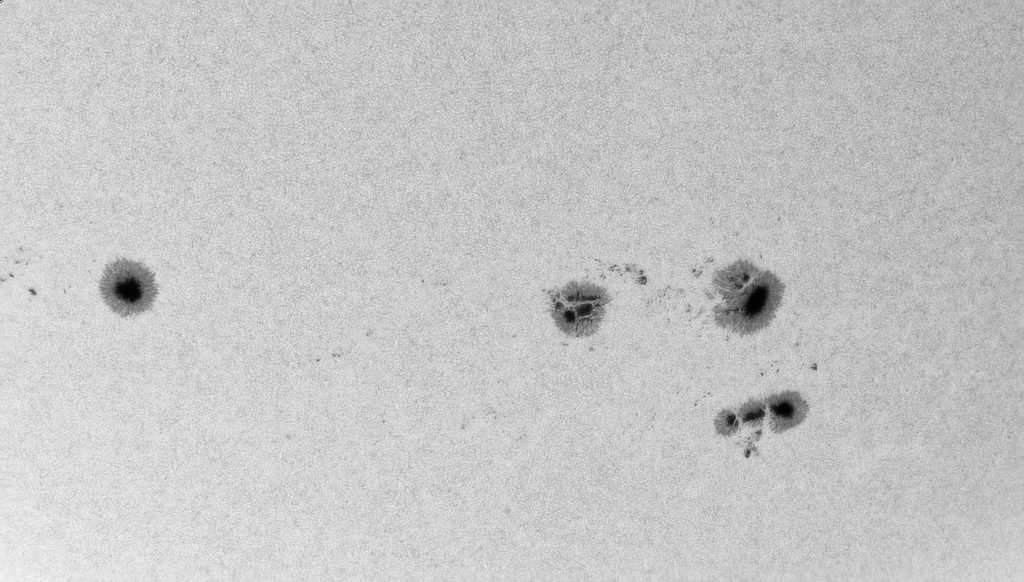

Even before the advent of the telescope, diligent astronomers knew about dark spots on the visible surface of the Sun – sunspots. We now understand that sunspots are like the ‘hurricanes’ of the photosphere, large storms not of rain and wind, but of intense magnetic activity caused by twisting tubes of magnetic flux deep within the Sun. These tubes wind through the innards of the sun and pop out into the surface from time to time. When a magnetic tube pops through the surface, it interrupts heat flow from deeper layers in the Sun and drops the local temperature to about 4,500 K, cooler than the 5,700 K temperature of the surrounding gas. That’s what makes a sunspot dark: it’s simply cooler than the rest of the photosphere.

In the mid 19th-century, after many years of observation, the German apothecary-turned-astronomer Samuel Schwabe noticed the number of sunspots rises and falls in nearly regular 11-year cycles. In peak years of the cycle, he found, there were spots visible on the Sun most days, and hundreds of spots and groups of spots during the course of a year. In lean years, roughly 5.5 years after the peak, there were weeks or months when astronomers saw not a single sunspot.

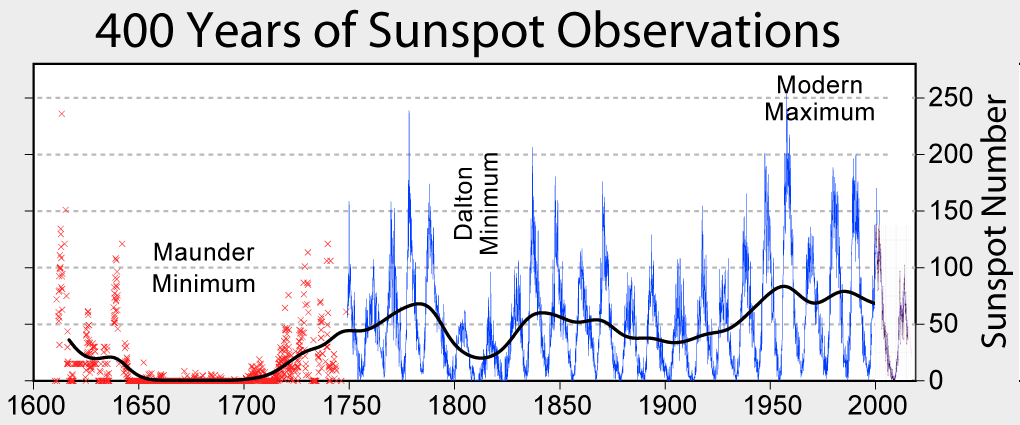

This regular cycle was traced back to the earliest telescopic observation of the Sun in the 1600′s, and has been recorded in increasing detail by modern astronomers right up to the present day. The diagram above shows a measure of the sunspot number over time since the 17th century. The 11-year period is clearly visible.

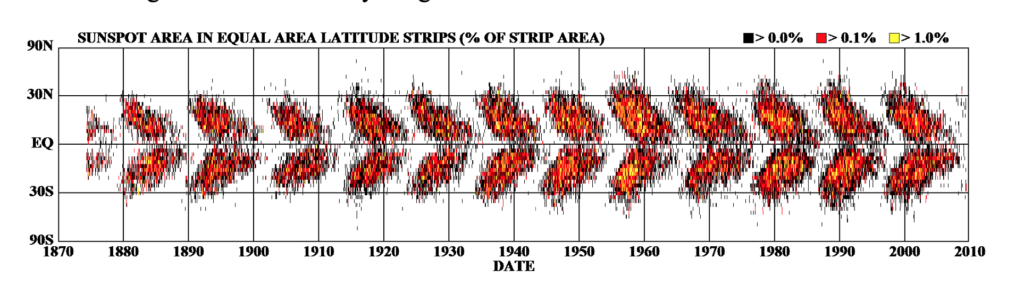

What’s even more interesting is where the sunspots occur on the solar disk. As the number of sunspots rises from a minimum, the spots appear north and south of the solar equator, usually in the mid solar latitudes around 40 degrees. As the cycle continues, sunspots appear closer to the equator until at the next minimum, most spots appear in a narrow band at the equator. Then, it all starts over again. A plot of the position of sunspots over time, shown below, is called the Maunder diagram or the “Butterfly Diagram”.

This periodic change in the number and position of sunspots was a striking discovery. And it’s not just the number of sunspots that varies every 11 years. The sunspot cycle also matches up with other activity on the Sun, including violent mass ejections, the size and extent of the outer reaches of the sun called the corona, and the intensity of light and charged particles the Sun blasts out into space to affect the atmospheres and magnetic fields of many planets in the solar system, especially Earth.

The solar cycle seems to be but a symptom of a complex and dimly understood dynamic process inside the Sun called a “solar dynamo” that generates the Sun’s global magnetic field. To make matters even stranger, the magnetic field seems to flip its polarity once every two sunspot cycles, or 22 years, which means the magnetic polarity of the sunspot pairs on the solar disk flips direction from cycle to cycle.

Sunspots cycles are assigned numbers by astronomers starting with the cycle of 1755. In December 2019, the Sun began its 25th cycle which will peak in 2024-2025, approximately before moving on to the next minimum in 2030. The past few solar cycles have displayed relatively few sunspots compared to past cycles over the last century. No one knows why. There have been past periods of quiet on the Sun with few sunspots. The Maunder Minimum from 1650-1720 and the Dalton Minimum in the early 19th century had very few sunspots. They also coincided with a marked cooling of the Earth’s climate. Again, no one knows why. Some predictions show that solar cycle 25 will be more active that cycle 24 and 23, but still relatively quiet.

Solar Flare X1 from AR2994 in Motion from Miguel Claro on Vimeo.

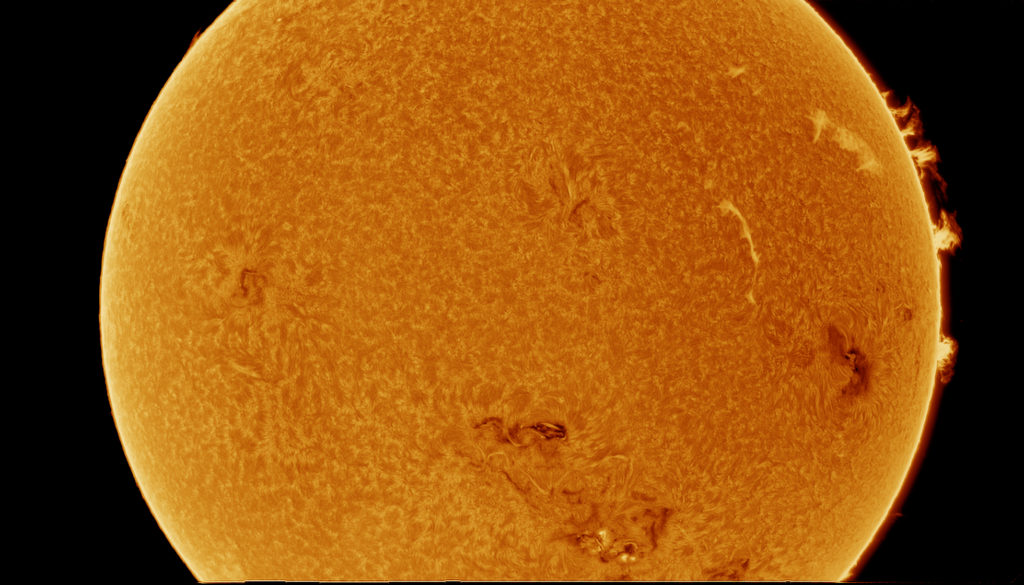

Still, there will be plenty to see. With a good white-light solar filter, observers with a small telescope will see more sunspots and associated structures in the Sun’s photosphere in the coming years. And observers with a dedicated solar telescope with a specialized ‘Hydrogen Alpha’ solar filter will see increased numbers of prominences and filaments and other activity in the ethereal chromosphere, a layer just above the photosphere. The video above shows a remarkable solar prominence and flare on the Sun’s limb on April 30, 2022 captured by the Portugese astrophotographer Miguel Claro. He captured these images and the associated video with off-the-shelf equipment available to amateur astronomers – and a whole lot of skill in post-processing. Yes, it’s going to be fun to watch as solar cycle 25 continues to do its thing…

Share This: