“There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen”, said V.I. Lenin. That, in a way, is what October feels like for stargazers and skywatchers who have enjoyed wave after wave of auroral displays, massive sunspots across the solar disk, and a bright, long-tailed comet in the morning and evening skies.

The month began with a parade of large sunspot groups passing across the visible face of the Sun. A few triggered solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CME) that blasted a stream of energetic charged particles towards Earth. An X9-class flare and CME on October 4 caused radio blackouts on Earth and a spectacular display of aurorae on Oct. 7-8. On the 7th, I set up to snap images of the Andromeda Galaxy, vaguely aware that a few aurorae might appear later in the night. From inside the house, I captured a quick test image of the galaxy to check focus. But the image revealed only a uniform lime green that nearly overwhelmed the camera sensor. I went outside, looked up, and saw aurorae covering most of the sky, from the north down to the southern horizon. There were curtains, streamers, isolated patches, and rivers of green and deep burgundy that seemed to flow from the southeast. Best of all, an auroral corona lay almost directly overhead near the constellation Lyra that gave the impression of standing under a waterfall of light. It went on for hours.

A few images of aurorae borealis as seen from Calgary, Canada on the nights of Oct. 7 and 10, 2024. Image credit and copyright: Brian Ventrudo.

The Sun ejected another X-class flare and CME on the 7th that triggered an even bigger auroral display in much of the world on Oct. 9-10. Observers in California, Australia, and Arizona caught glimpses of this show. High haze obscured my view somewhat, but the aurorae were bright enough to see even when standing next to a streetlight. The streams and patches of aurorae on this night flickered much faster over just a second or two as an intense stream of charged solar particles pounded and kneaded the Earth’s magnetic field. It looked like the parts of sky were sending messages in morse code.

While aurorae are hard to predict precisely, more are on the way, no doubt, as the Sun reaches the peak of its 11-year cycle of magnetic activity. Check the always useful Spaceweather.com for updates on solar and auroral activity.

Comet C/2023 A3 Meets Expectations

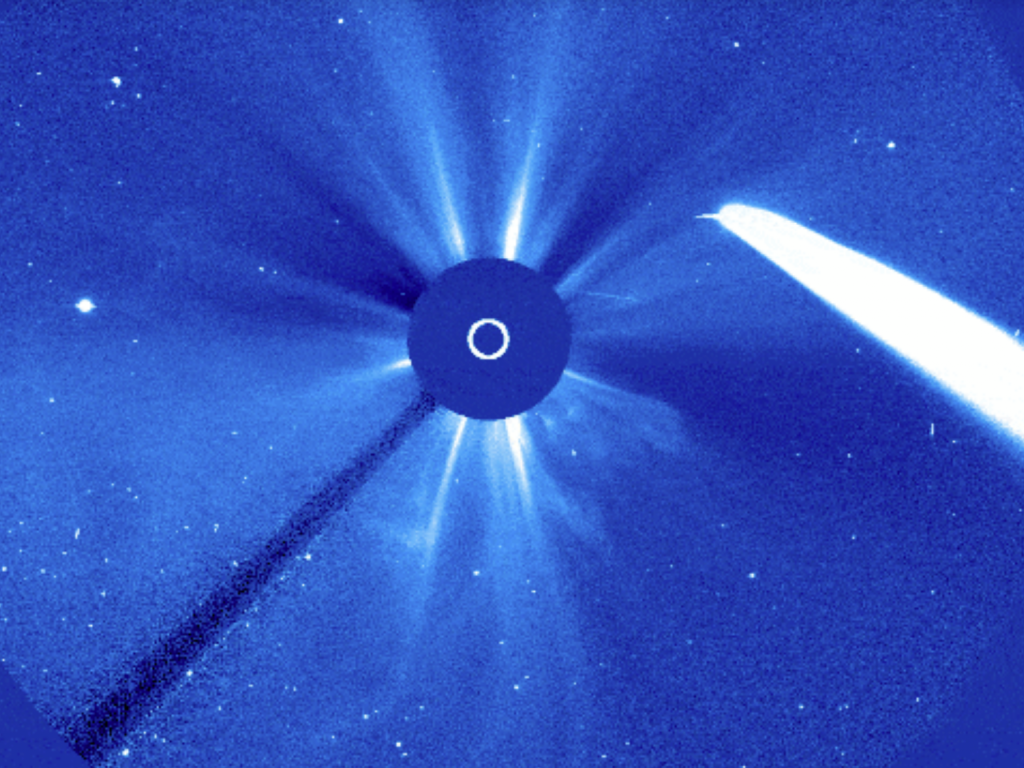

And then, there’s Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan–ATLAS). As the comet passed the Sun, NASA’s SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory) satellite captured the comet in its field of view along with a CME on Oct. 9-10 – see above. Some worried that the comet might disrupt the comet’s tail, but it appears to have emerged unscathed. But by all accounts, this little comet has met expectations for an excellent apparition first in the morning sky in the southern hemisphere in late September, and now in the evening sky in the northern hemisphere from around Oct. 10 onward.

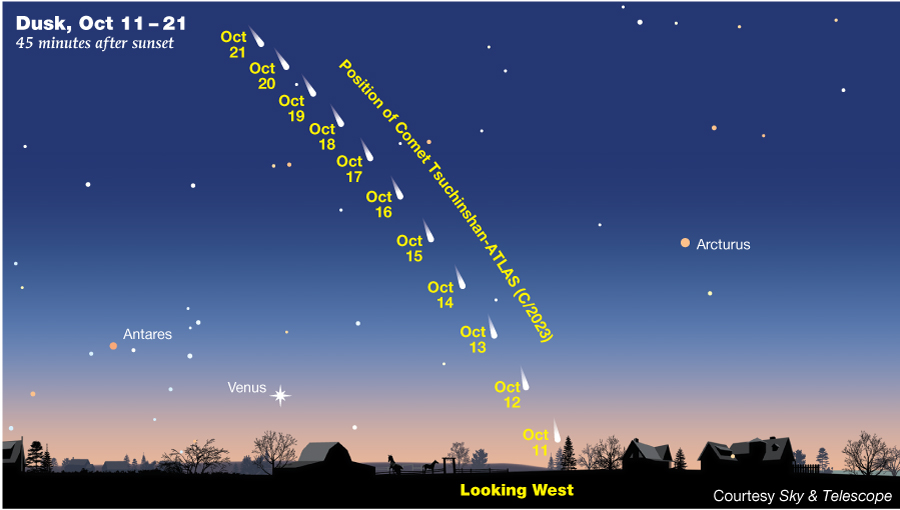

Comet C/2023 A3 made its closest approach to Earth on Oct. 12 at a distance of 77 million kilometers. As it passes the Earth, it gets dimmer but higher above the western horizon and therefore easier to observe. I first spotted it on Oct. 13 in the hazy twilight glow with a pair of binoculars. Clearer sky on Oct. 14 and the comet’s higher elevation made it easy to find about 15 degrees to the right of Venus in the west-southwestern sky after sunset. By 8 p.m. local time (about 75 minutes after local sunset) it was easy to see with the naked eye and included a pinpoint head and tail about 10-15 degrees long. Current estimates place its brightness at about magnitude +0.5. The coma is considerably fainter than Arcturus which shines above and to the comet’s right, but it’s not a challenge to see it once the sky gets darker. Images show the comet’s long tail and clear hints of a needle-like anti-tail emerging from of the comet’s head and pointing towards the Sun. It was an impressive sight, at least as good as Comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) in 2020.

The comet continues to rise and dim over the coming days, but there’s plenty of time to see it. The chart above, courtesy of Sky & Telescope magazine, shows where to find it. Look for it about 30 minutes to about 2 hours after sunset after which it begins to set. And if you want a photo, even a decent smartphone camera will do the job! Good luck!

Share This: