It had been two years since I’d had a good look at the summer Milky Way. At my latitude, it doesn’t get dark enough for visual stargazing from late May to late July, and clouds, smoke, moonlight, and the vicissitudes of life disposed of the remaining late summer nights. But this week delivered what I’ve long awaited – a promising forecast of two nights with a crystal-clear atmosphere and no moon. The excuses were over – it was time to drive an hour west of town to my favorite dark-sky site with a telescope, a bag of eyepieces, and a star map in the back seat. If I was going to see the Milky Way before winter comes, it was now or never.

With a purely manual mount and no electronic aid, I was a bit concerned I’d be a little rusty in my star-hopping skills. Stargazing is, after all, a perishable skill. But I had a deeper concern: would I even enjoy it anymore? I’d felt indifference creeping into my backyard observing sessions where it’s hard to see much detail in deep-sky sights in the slate-grey suburban skies. Maybe, I thought, it was time for a long break from astronomy. Or worse – a permanent break, perhaps to take up another pastime like birdwatching, golf, or square dancing. But as I arrived at my site with eyes partially dark adapted from the drive, I hopped out of the car, looked up at the silver-white band of the Milky Way stretching from overhead down to the southwestern horizon, split by the dark ‘Great Rift’ and knotted with star clouds and nebulae, and muttered under my breath, “Oh. My. God.” Yes, I remembered right away why I do this. What a difference dark sky makes.

My tool of choice was a 100-mm APM binocular telescope, a spectacular instrument that hasn’t seen nearly enough starlight. Early tests of this binoscope from my backyard were encouraging. Our brains are built for two-eyed observing, and this scope revealed far more detail, and with more comfort and ease, than a regular ‘cyclops’ telescope of much larger aperture. This was the binoscope’s first trip to dark skies. I popped in a pair of 24mm Panoptic eyepieces that delivered a magnification of 23x and a 2.8o field of view, manhandled the scope onto its fork mount, and got down to business.

I turned first to Sagittarius setting quickly in the southwest. Although less than 10o above the horizon, the dazzling pair of emission nebula M8 (the Lagoon) and M20 (the Trifid) appeared crisp and spectacular in a single field of view. The spanking new star cluster embedded in M8 along with its eponymous dust lane were clearly visible. M20 revealed less detail but looked like a tiny Chinese lantern with the lovely open cluster M21 just off to the northeast.

Further north I aimed at two more star factories, M17 and M16, the Swan and Eagle Nebulae, respectively. The Swan, in Sagittarius, showed its characteristic check-mark shape while M16 (in Serpens) was more diffuse but showed its wing-like structure. I saw no sign of its famous Pillars of Creation at this magnification, but its embedded cluster of young blue-white stars was easily visible. All four of these grand emission nebula lie more than 5,000 light years away, about four times the distance to the Orion Nebula (M42).

While a 100mm scope isn’t big enough to resolve most globular clusters, the rich but loose globular M22 easily showed a salt-and-pepper granularity to its core in the 100-mm binoscope. Rod Mollise calls Messier 22 the ‘Arkenstone of the Sky’ after the gem sought by Thoren Oakenshield in The Hobbit. When cut by and fashioned, it appeared as …”ten thousand sparks of white radiance, shot with glints of the rainbow”. M22 is arguably the most visually appealing globular accessible to northern-hemisphere stargazers and well worth lingering over.

Just above the top of the “Teapot” of Sagittarius and south of M17 lies one of my favorite sights in all of nature, the Little Sagittarius Star Cloud, or Messier 24. It’s not a coherent object in its own right like a star cluster, but rather a window in the intervening dark clouds of the Milky Way to a distant patch of stars deeper inside the galaxy some 9,000 light years away. Were it not obscured by intervening dust clouds, the entire band of the Milky Way would appear this bright. At a size of about 2ox3o, it nearly filled the field of view and appeared as a sparkling patch of blue-white stars against a diffuse background of fainter unresolved stars. Two dark oval foreground dust clouds, Barnard 92 and Barnard 93 were plainly visible on the northwestern and northeastern corners of the cloud.

At this point, I pulled back from the eyepieces for a rest and sip (of water, I swear) and looked around at the nearby trees and river in the near total darkness. Then I slowly moved my eyes back towards the eyepieces – they appeared as a porthole hanging in space before me like a hidden passage into the heart of the Milky Way, which in a way is exactly what they were, a visual passage available for the increasingly few who choose to take it.

Now in the grip of a lust for rich star fields, I turned to another star cloud, the anvil-shaped Scutum Star Cloud just off the tail of the constellation Aquila. Nearly as large as M24 and just as dazzling, this vista partially resolves into a blanket of stars with the tight but rich open cluster M11 on its eastern edge. Even at 23x, with averted vision, I could resolve the superb M11. The northern and western edges of the star cloud are clipped by coal black dark nebulae, especially the large crescent-shaped Barnard 111.

Looking back westward, I enjoyed a quick look at three lovely open star clusters in western Ophiuchus near the asterism called Taurus Poniatowski. The jumbled cluster IC 4665 appeared as I’d left it a couple of years ago, a group of stars arranged like a backwards “HI”. The other two, sometimes called the Ophiuchus double cluster, lay at opposite ends of the same field of view. The larger but looser IC 4756 showed its ragged linear backbone, a lovely object for sure, but its partner NGC 6633 was prettier and more uniform with all manner of patterns among its stars.

It was getting late, so I took a quick look at three favorites, the enigmatic globular cluster M71 in Sagitta, the adjacent planetary nebula M27 (the Dumbbell), and the small globular M56 in Lyra, all three of which lie in spectacular star fields. I also turned to a childhood favorite in Lyra, M57, another dying star tiny at 23x with a just a hint of ring-like structure.

Then I turned to an object I’d never seen before, the dark nebula Barnard 143 or ‘Barnard’s E’ just west of the star Tarazed in Aquila. (A hat tip to Chris and Shane at the Actual Astronomy podcast for this one). This inky-black nebula is a snap to see in dark sky and looks very much like its namesake letter. A real treat. Further south in Aquila, I spotted the longer arc of the less obvious Barnard 138 about 10o to the southwest and just below the star Delta Aquilae.

At this point in a good stargazing session, a certain level of begin mania begins to take hold as the observer hops from sight to sight. I recalled what Timothy Ferris said in his book Seeing in the Dark as he took in a series of his favorite galaxies during a visual observing session: “I felt absurdly happy, like the early French balloonist who, once aloft, refused to come down.”

So onward I floated.

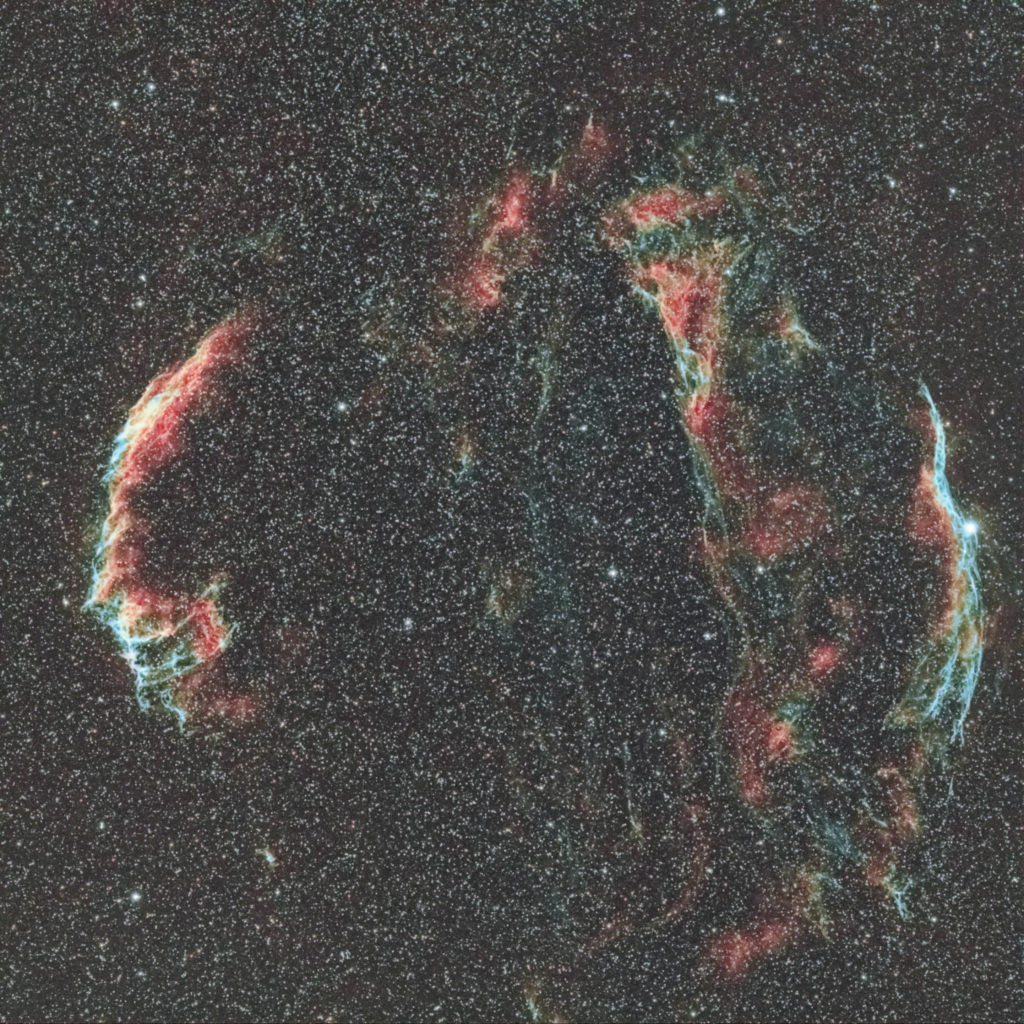

In Cygnus I turned my optics to the shimmering shape of the North America Nebula (NGC 7000) just a few degrees off Deneb. I could just see it without optical aid, and it easily emerged in the binoscope where it nearly filled the entire field and assumed its namesake shape. It appeared especially striking when I threaded a pair of UHC (light pollution) filters into each eyepiece – just like a photograph, only better. It was the same story with another favorite, the lovely Veil Nebula complex off the eastern wing of the celestial swan. With the UHC filters, I could see hints of knotted structure in the eastern Veil (NGC 6992), the ‘witch’s broom’ shape in the western Veil (NGC 6960) along with the star 52 Cygni, and hints of the brightest parts of Pickering’s Triangle in between.

Sleep beckoned, but I turned quickly to sights to the east and south. Most planetary nebulae are tiny, but the Helix Nebula (NGC 7293) in Aquarius presented an astonishingly large image, nearly as large as the full Moon, with a hint of a darker core inside a brighter perimeter in a sparse region of sky.

As a test of the telescope and sky conditions, I had a quick glance at NGC 7789 in Cassiopeia. Completely invisible from my backyard, in dark sky this ancient open star cluster was an easy sight with a uniform grainy texture. It’s one of the dozen or so lovely open star clusters in Cassiopeia. The rest, alas, had to wait for another night.

The binoscope earned its keep when I turned it to the Andromeda Galaxy (M31). Though I’d seen it in larger refractors, I’d not seen such a detailed view with a small telescope as I did during this observing session, a testament to the observing conditions and the advantage of two-eye observing. The galaxy spanned the full field of view and then some, and I easily spotted its two companion galaxies M32 and M110 and hints of dust lanes and spiral structure in this nearest major galaxy.

At last, I turned to the Double Cluster (NGC 869 and NGC 884). They were an astonishing sight in the binoscope, with a brilliant 3D appearance as if I could reach out and pluck them from in front of the objective lenses. No photograph can do justice to the visual appearance of these new star clusters, or to most of the brighter objects on this tour. Some 7,000 light years away, this unequalled pair would span nearly a quarter of our night sky if it were as close as the Pleiades. Even now it’s a pleasure to conjure in my imagination an image of this immense collection of newly minted stars.

As the night came to an end, and the night after too, I was deliriously tired. Yes, I had work to do and deliverables piling up. But for the first time in a long time, I felt well, invigorated, refreshed even, as if I’d been on an exhausting but absorbing vacation. It called to mind the words of Leslie Peltier, author of Starlight Nights:

“Were I to write out one prescription designed to alleviate at least some of the self-made miseries of mankind, it would read like this: “One gentle dose of starlight to be taken each clear night just before retiring.”

It’s worth the effort, fellow stargazer.

Share This: