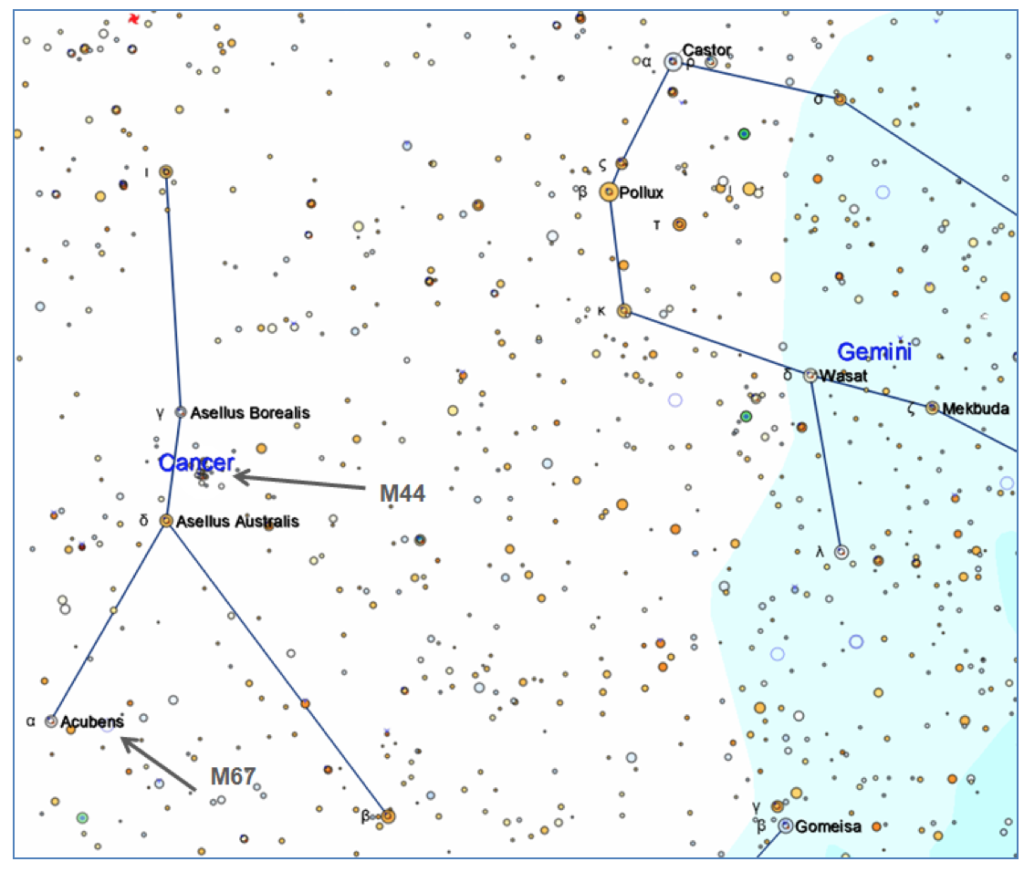

Nearly overhead in the mid-evening hours of northern spring (and low over the northern horizon in the southern hemisphere), the constellation Cancer is the faintest of the twelve constellations of the zodiac. Many casual stargazers pass it by when looking from bright Gemini to the striking group Leo to the east. In city skies, the constellation is hard to see at all. Despite its inconspicuousness, there are some excellent sights in Cancer within reach of a telescope, including the superb star cluster M44, the Beehive Cluster, and the intriguing M67, one of the oldest known open star clusters.

The Beehive Cluster

One of the finest open star clusters on the Messier list, the Beehive is easily visible to the unaided eye in dark sky as a misty cloud just west of the mid-point between the stars Asellus Borealis and Asellus Australis, the northern and southern ‘donkeys’. These stars represent the animals which Dionysus and Hephaestus rode in a battle between the gods of Olympus and the Giants. The fearsome noise of the two donkeys frightened away the giants, and the Olympians placed the aselli in the heavens. The stars feed at a heavenly manger – the Beehive cluster – which is also called the Praesepe (“PRAY-see-pay”), Latin for ‘manger’.

One of the few star clusters known since antiquity, the Beehive was called the “Little Cloud” or “Cloudy Star” by the ancient Greek astronomer Hipparchus. The ancients used the cluster as a weather indicator. If it was invisible, as high cloud crept in as the air pressure fell, then violent storms were said to be on the way. Unlike the Pleiades, M45, this cluster can’t be resolved into individual stars with the unaided eye. Its true nature and striking beauty are revealed only with help of binoculars or rich-field telescope. Galileo was first to turn a telescope toward this “nebulous” object, and reported: “The nebula called Praesepe, which is not one star only, but a mass of more than 40 small stars.”

The cluster lies about 580 light years from Earth and stretches 16 light years across. It appears about 1.5o across (about 3x the size of the full moon), so examine it with your binoculars or telescope with a low-power eyepiece to see its full glory. It is a very fine object for binoculars.

About a dozen of the cluster’s constituent stars shine brighter than magnitude 7; the brightest is epsilon Cancri (magnitude 6.3). Three dozen more shine between magnitude 7 and 9. With larger telescopes, nearly 1,000 stars have been confirmed as members. Astronomers determine which stars are members of the cluster by measuring the common motion of the stars. If they’re all going in the same direction, they’re assumed to be from the same cluster.

The Beehive emerged out of a great diffuse gaseous nebula some 730 million years ago. That’s long enough for many of its brightest and most massive stars to fall towards the center of the cluster, a process known as dynamical relaxation. Given its great age, the cluster also features many red giant stars that have evolved off the main sequence and are nearing the end of their lives.

Some studies suggest the Praesepe has a common origin with the Hyades cluster which forms much of the constellation Taurus to the west. The two clusters have since separated, but they’re still headed in the same direction.

Because of its nebulous appearance to the unaided eye, the ancient Japanese believed the cluster was a lump of souls, and the sight of it terrified them. It’s called seki shiki in Japanese which translates as “piled corpse spirits”.

Messier 67 – An Ancient Open Cluster

The Beehive is the most famous Messier object in Cancer, but it’s not the only one. Messier 67 lies in the southern regions of this small constellation some 1.7o west of α (alpha) Cancri, also called Acubens. M67 is easily visible with binoculars or a finder scope. At moderate magnifications, a 3-inch scope shows a misty splash of unresolved stars. A 4 to 6-inch scope reveals 40-50 faint stars spread over almost half a degree. The brightest star is 8th magnitude and shines yellow-orange on the cluster’s northern edge.

The cluster likely retains some 500 stars, an amazing feat given its great age of 2.5 billion to 5 billion years. That’s much older than more typical open clusters like the Pleiades which formed just 100 million years ago. Very few open star clusters survive to this age before their stars are tugged away by gravitational interactions with passing stars or gas clouds. M67 may remain intact because it lies about 1,500 light years above the plane of the Milky Way where it avoids interactions with other massive bodies that might otherwise strip the cluster of stars over the eons. The cluster lies almost 3,000 light years from our solar system.

In 2010, a detailed study of M67 led to an intriguing hypothesis – that our Sun was once a member of M67. The age of the cluster is about right, and some of the cluster’s stars have a composition very much like the Sun. But more recent analysis of the relative speeds of M67 and the Sun throw cold water on this idea. Our star most certainly formed in an open cluster like M67, but that cluster has yet to be identified. Or more likely, our home cluster has long since dispersed into the wider Milky Way.

Share This: