The Pleiades star cluster in the constellation Taurus is one of a handful of objects in the heavens that never fail to amaze and inspire even the most experienced observers. As beautiful in an inexpensive pair of binoculars as in images from big professional telescopes, this star cluster presents visual observers an especially lovely sight with stars of an unearthly blue ensconced amid a faint frost of nebulosity. If there were more objects like it in the night sky, there would be a lot more amateur astronomers in the world.

The Most Famous Star Cluster

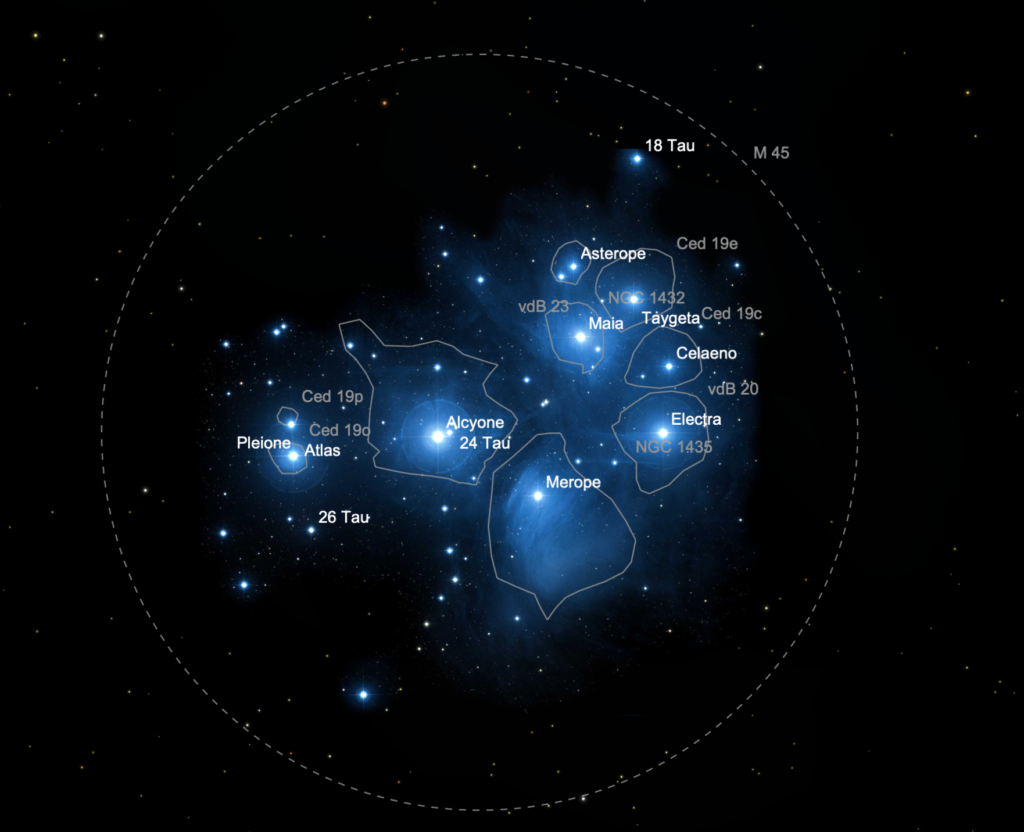

Sometimes called the Seven Sisters, the Starry Seven, and the Seven Atlantic Sisters, the stars of this small dipper-shaped cluster take their names from the ancient Greek god Atlas, his wife Pleione, and their seven daughters. The star Atlas marks the handle of the dipper-shaped cluster. The stars Alcyone, Maia, Electra, Taygeta, and Merope form the small bowl. Near Atlas lies Pleione, his wife of mythology. The fainter star Sterope (sometimes called Asterope) forms an equilateral triangle with Maia, and the star Celaeno lies between Taygeta and Electra. In the Mediterranean world, the cluster took its name from pleiad, the ancient Greek word for sail since its appearance in the morning spring sky heralded the beginning of sailing season.

Most naked-eye observers can see six stars of magnitude 3.0 through 5.5 in the Pleiades – Atlas, Alcyone, Merope, Maia, Electra, and Taygeta. However, many ancient cultures from Europe to Japan to Australia once claimed to see seven stars here. The Greek poet Aratus in the 3rd century B.C. wrote, “Their number seven, though the myths oft say, and poets feign, that one has passed away.” Some speculate that Pleione, a short-term variable star, may have shone brighter in classical times. A more recent explanation, based on star motions measured with the European Gaia space telescope, suggest Atlas and Pleione were long ago more widely separated and easier to resolve into two distinct stars with the naked eye. It may be, however, the confusion about the number of stars in the Pleiades may come down to a matter of the visual acuity of the observer. Modern stargazers with very dark sky and excellent vision can spot nine or ten stars in total. Some claim to see as many as 18!

As such a prominent star cluster, one that lies near the ecliptic, the Pleiades has been known since the dawn of history by cultures all over the world. A study of the mythologies based on these stars and their appearance in literature around the world make for fascinating reading. Some examples:

- Polynesian peoples called them matarii or matariki (“little eyes”) and held they were once a single star split into six during a battle among the gods

- Medieval northern European cultures, including the Vikings, presumably occupied with the essentials of life rather than poetry, called them the ‘Hen and her Chicks’

- Kiowa and Cheyenne of the American great plains believed these stars were seven maidens placed into the sky and protected from harm by the Devil’s Tower (in Wyoming)

- Finnish and Lithuanian stargazers saw them as a sieve or net (in Tolkien’s The Hobbit, they were called “The Netted Stars”)

- The Quechua and other cultures in the Andes called them the ‘Storehouse’ since their appearance in the morning sky (in May) coincided with harvest time

- In Japan, these stars were called subaru, which means unity (the Subaru car company was named when five smaller firms merged into a larger sixth firm, Fuji Heavy Industries).

In my current part of the world, southern Alberta, Canada, these stars were known to the Blackfoot First Nation as the ‘Orphan Boys’, fatherless boys rejected by their tribe and befriended by a pack of wolves who became their only companions. The boys found the sadness of their lives hard to bear, so they asked the Great Spirit to let them live and play together in the sky, so he placed them there as a small cluster of stars. As a reminder of their cruelty, the cruel tribe members were disturbed every night by the howling of the wolves who missed their lost human friends.

Seeing the Pleiades

The Pleiades is visible in the evening hours from December through April, and observing the cluster requires no particular knowledge or experience. Spectacular with or without optics, the Pleiades look best in a small wide-field telescope at low magnification that can take them all in with enough surrounding sky to frame them nicely. An 80mm refractor shows about 80-100 stars. Look for close pairings of stars, especially Asterope, Atlas and Pleione, Taygeta, and a faint pairing near the center of the bowl. Any decent pair of binoculars also give a spectacular view.

Physically, the Pleiades are quite young. With an age of 100 million years, the cluster still contains many bright blue and blue-white stars. There are a few more evolved stars that have swelled and turned yellow or orange. A white and orange pair, ADS 2755, can be seen in the bowl of the dipper. And a 6th-magnitude orange star is visible about 0.3o north of the bowl.

Look also just south of Alcyone for a lovely chain of stars that turns south-southeast.

The last two stars in the chain appear orange or yellow orange. The first star in the chain is the fine double star Struve 450 (Σ450). The primary is magnitude 7.3 separated by 6.1” from the 9th-magnitude secondary. A small scope at 75-100x should split the pair nicely. The star Sterope is also a widely-split pair, just barely split without optics by keen-eyed observers. Taygeta is also a wide double. The primary is magnitude 4.3, while the secondary, some 69” north, shines at magnitude 8.3. Any telescope at low power can split this pair.

Images of the Pleiades show a beautiful lacework of nebulosity around these stars, a result of the cluster passing by chance through a cloud of interstellar dust. Visual observers can see hints of this nebulosity in dark and pristine sky with a small telescope. The easiest patch of nebulosity appears around the star Merope. The Merope Nebula, or NGC 1435, appears frosty-white and just barely brighter than the background sky. It’s sometimes confused with the effect of dew on a telescope’s objective lens or mirror or eyepiece, so to make sure you’re really seeing the nebula, move the telescope from the Pleiades to the Hyades and back. If you see nebulosity around the stars of the Hyades, you have a dew problem. If you only see a faint glow around Merope, you’re seeing something real.

Like all open star clusters, the Pleiades will get buffeted and tugged by gravity from passing stars and gas clouds. Over the next few hundred million years, its stars will get pushed out of the cluster and make their way around the Milky Way alone.

Share This: