Conjured by Johann Hevelius in the late renaissance, the dim, linear constellation Lynx fills in the space between the much larger constellations Gemini, Auriga, and Ursa Major, just out of the plane of the northern Milky Way. While it doesn’t much resemble its namesake and contains no bright stars, Lynx harbors one of our galaxy’s most distant outliers, the famous ‘Intergalactic Wanderer’ (NGC 2419), a globular cluster that roams the desolate expanse between the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy.

NGC 2419 is a favorite of backyard stargazers because of its great distance. Messier missed this 10th-magnitude cluster, but it lies within reach of a small telescope. It was discovered in the late 18th century by William Herschel who suspected it was a diffuse nebula. A century later, the Irish gentleman-stargazer Lord Rosse carefully observed the cluster with his immense 72” reflector and partially resolved it into stars. Rosse believed it was a globular cluster, but this wasn’t confirmed until 1922 when Lowell Observatory astronomers captured it in detailed photographs.

A Distant Outlier of the Milky Way Galaxy

During his research that ultimately discovered the size of the Milky Way, Harlow Shapley first estimated the distance to NGC 2419 in the 1920s. By measuring the period and brightness of a handful of its variable stars, he determined a distance of 99,000 light years. This has since been updated to a staggering distance of 275,000 light years from our solar system and 300,000 light years from the center of the galaxy. That’s more than three times the diameter of the Milky Way’s visible disk, and more than twice as far as the Large Magellanic Cloud, the bright and nearby dwarf galaxy visible from the southern hemisphere. Only three of the Milky Way’s 147 globular clusters are more distant. Palomar 3 and Palomar 4 lie at a distance of 300,000 and 360,000 light years from our solar system, respectively, while Arp-Madore 1 is about 400,000 light years away.

Upon first measurement of its distance, Shapley conjectured that NGC 2419 might be gravitationally unbound to the Milky Way or any other galaxy. He named it the “Intergalactic Tramp” in the sense of one that travels from place to place without aim. Its name has since been updated. The Canadian astronomer Bill Harris of McMaster University, in his detailed 1999 review of our galaxy’s globulars, found that while NGC 2419 is an outlier in terms of location and distance, it is indeed bound to the Milky Way.

An acknowledged expert on globular clusters, Harris made a more obscure contribution to science by serving on my doctoral advisory committee in the early 1990s where he ensured a level of quality control before McMaster sent me on my way with a degree in hand. He provided me some astronomical grounding because I was an outlier myself in those days, a student of engineering physics using lasers to study the spectroscopy of small molecules of astrophysical interest, neither an astronomer nor a spectroscopist nor an engineer. But as Robert Heinlein once said, ‘specialization is for insects.’

Seeing the Intergalactic Wanderer in a Telescope

While it appears dim because of its great distance, the Intergalactic Wanderer is intrinsically big and bright. It’s a full magnitude brighter, in real terms, than the Hercules Cluster (Messier 13), the brightest globular visible in the northern hemisphere. Were it at the same distance as M13, it would appear as large as the full Moon. By contrast, the next furthest globular, Palomar 3, is four full magnitudes fainter than the Intergalactic Wanderer despite lying only slightly further away. Still, NGC 2419 is about three times fainter, intrinsically, than our galaxy’s largest and brightest globular, the majestic Omega Centauri cluster, which in any case may not be a true globular cluster but the remnants of a dwarf galaxy torn apart by the Milky Way billions of years ago.

You can find the Intergalactic Wander about seven degrees north of the star Castor in Gemini. It’s barely visible in a 4” telescope to keen-eyed observers with dark sky. Two foreground stars of similar brightness form a tidy three-point line in the same field of view. With an apparent diameter of just 4’, it appears as little more than a dim and unresolved smudge, even with a 12” scope. The cluster’s stars average a brightness of 17th magnitude, so a large scope (16”) is needed to resolve individual stars visually in the outer halo.

Or you can swap out your eyepiece for a small camera and get a really good view. Even with a small and simple astronomy camera, it’s easy to quickly capture an image and resolve stars nearly to the core of NGC 2419, even in relatively light-polluted sky. I captured the image at the top of this article with a small ZWO ASI290MM camera and an 85mm refractor working at f/5.6. In this image the cluster resembles the much brighter M13 cluster when seen visually through an eyepiece in this same small telescope. The human eye is an amazing contraption, but it can’t hold a candle to sensitive modern electronics.

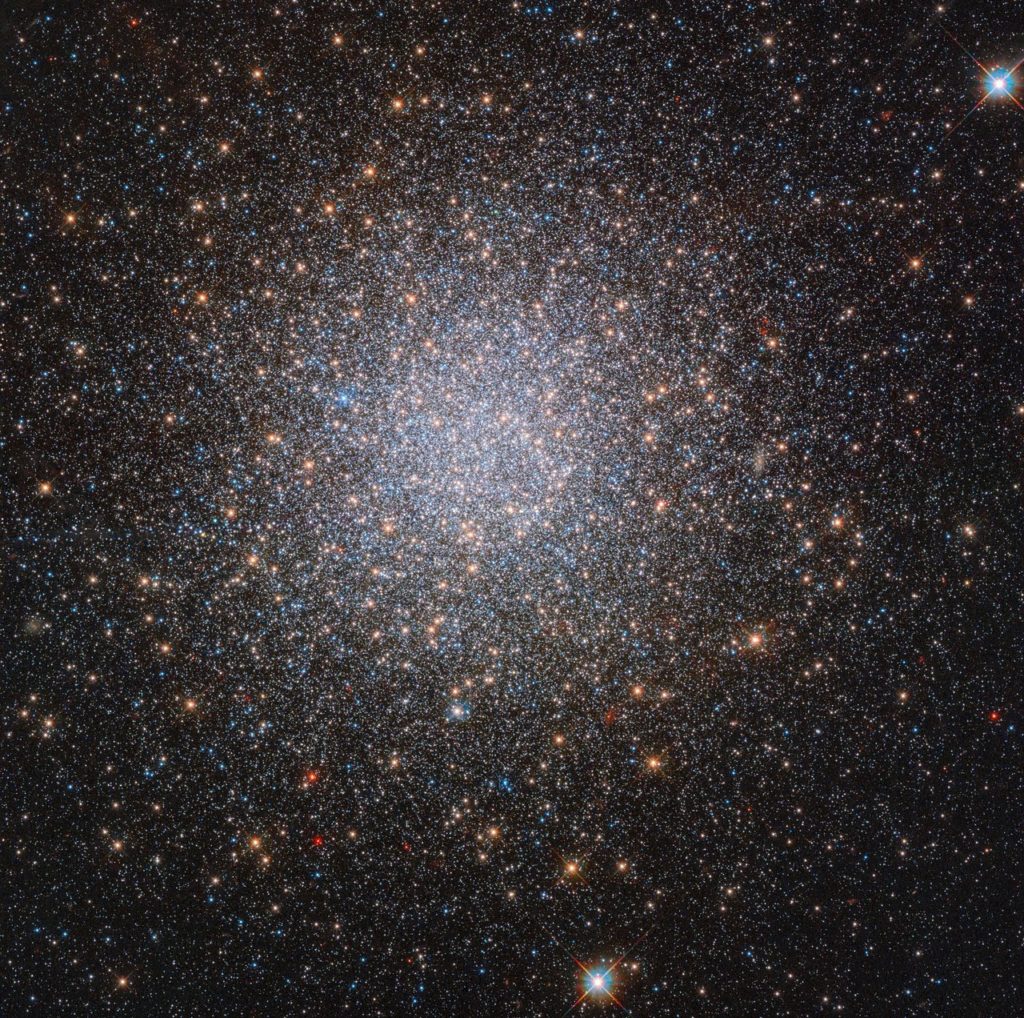

Of course, if you have a space telescope handy, you can get images of NGC 2419 like this:

A Bird’s-Eye View of the Milky Way Galaxy

The astronomical consensus suggests the component stars of most globular clusters were born together, at the same time, some 12 billion years ago. That means most of the stars of each globular cluster should have a similar chemical composition.

But a 2019 study suggests NGC 2419 has stars with two distinct chemical compositions. The stars in the inner regions of the cluster are more rich in helium than stars in the outer regions.

Why is this? Is this cluster a result of the merger of two smaller star clusters? And does this odd two-tone chemical make-up have anything to do with its great distance?

No one knows for sure, but it’s an important question. Ancient star clusters like the Intergalactic Wanderer bore witness to the formation of the Milky Way and they can help astronomers figure out how our galaxy assembled itself from smaller pieces more than 10 billion years ago.

The View of (and from) NGC 2419

The Intergalactic Wanderer lies in the opposite direction from most of the galaxy’s globular clusters in the constellations Sagittarius and Scorpius towards the center of the galaxy.

It’s roughly in the direction of the Andromeda Galaxy (M31), which lies about 2 million light years away. Given its proximity to M31 and its intrinsic brightness, NGC 2419 would rank as the brightest of the Milky Way’s globular clusters as seen from Andromedan skies where it would appear as a 14th magnitude speck in a hefty backyard telescope, assuming any Andromedans have backyards or telescopes. That’s a little fainter than Andromeda’s brightest globular, called G1, appears to us.

Looking in the other direction, an observer with a clear view and a dark sky perched in or around a star or planet in NGC 2419 would enjoy a spectacular ‘bird’s eye’ view of the Milky Way, which would span about 30 degrees of sky. Our sun, were anyone to look its way, would shine at an inconspicuous 24th magnitude, one of a few billion stars located in a faint spur of the Orion Arm of the Milky Way.

But is anyone out there looking back on such a spectacular vista?

No one knows for sure, of course, but the odds are against it. Like all globular clusters, NGC 2419 is composed of hundreds of thousands of ancient stars, all more than twice the age of the sun, which means they formed from material in the early universe with very few heavy elements such as iron and carbon. That might make it hard for earth-like planets to form. Planets around these stars would also endure frequent perturbations to their orbits from passing nearby stars in this densely-packed cluster, making them unstable environments for complex life (as we know it) to coalesce.

If it has no populated planets, and no nearby stellar neighbors, this fascinating galactic outlier must offer a great place to get away from it all for anyone with the know-how to get there. And even from its perch in intergalactic space, it still offers many clues about the early days of the Milky Way that astronomers hope to learn with the next generation of space and big ground-based telescopes.

Share This: