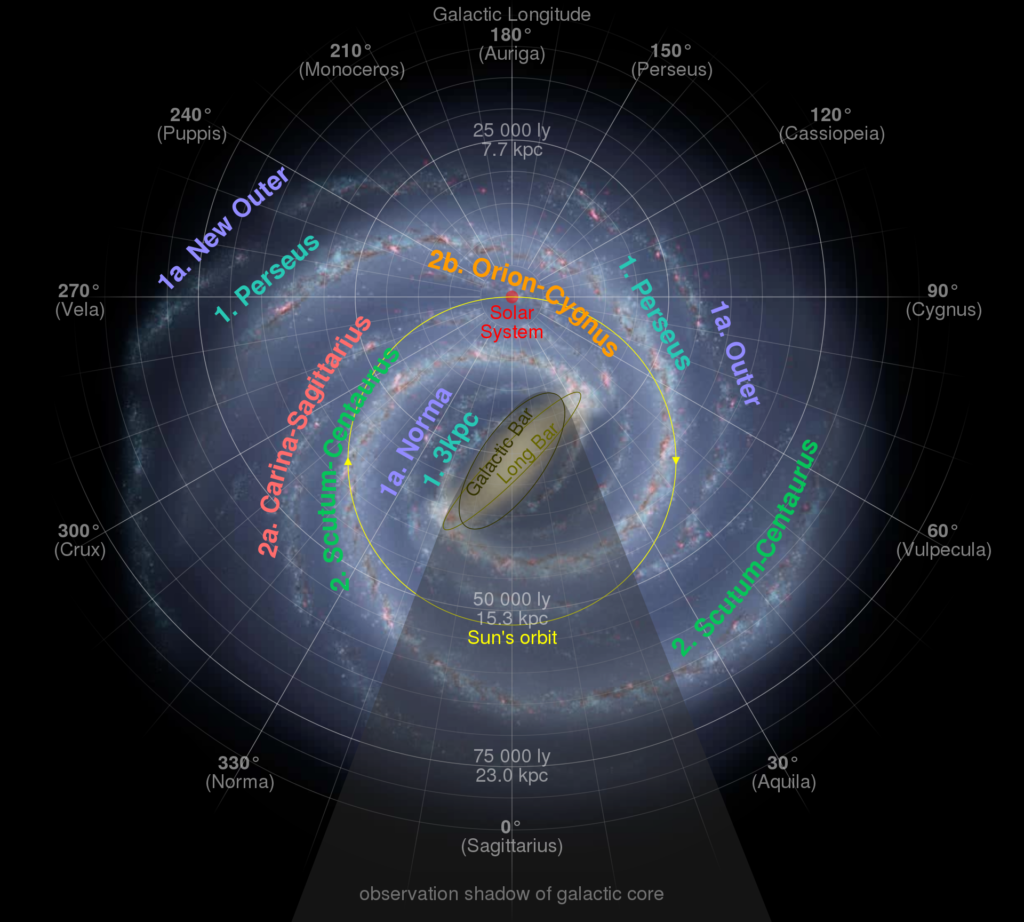

In the early months of each year, stargazers south of the equator enjoy a dazzling view of a rich part of the Milky Way, one that’s festooned with open star clusters, emission nebulae, and bright blue-white stars. Here, in the constellations Centaurus and Crux, we gaze into one of the two major spiral arms of the Milky Way, the Scutum Centaurus Arm, that originates from the long bar of ancient stars at the core of our galaxy.

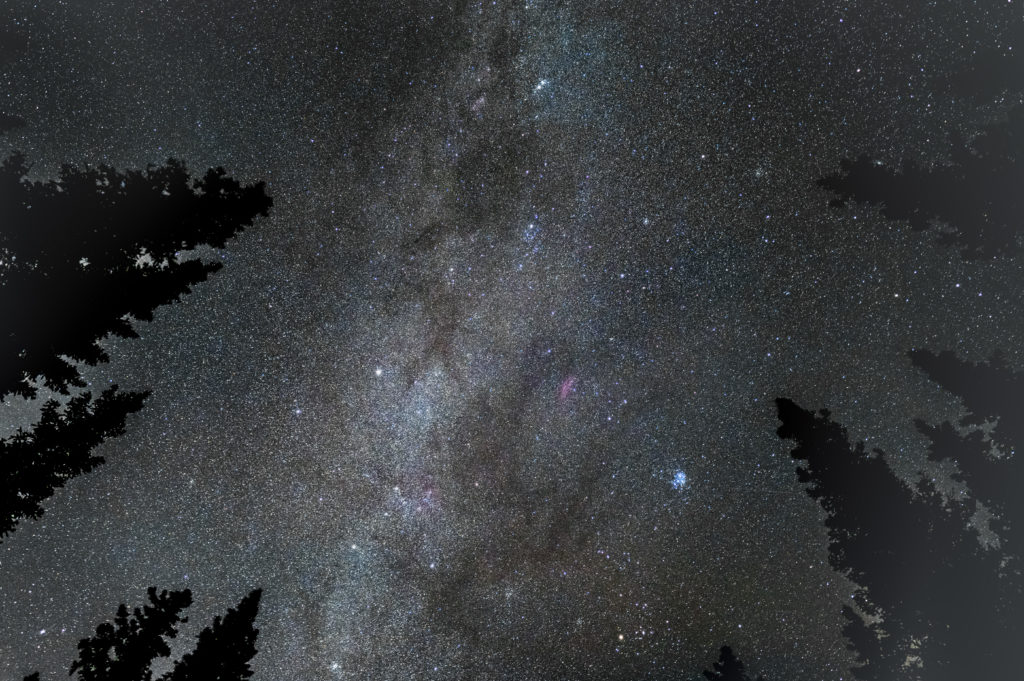

An observer looking overhead in the northern hemisphere sees a completely different perspective. Here the view lies in a direction away from the center of the galaxy into the outer reaches of the Perseus Arm, the second major spiral arm that emanates from the galactic core.

While not nearly as bright as the thick part of the southern Milky Way, the section of the Perseus Arm nearest to our solar system holds many wonders for visual observers with small telescope as well as astrophotographers.

About 6,400 light away at its nearest passage to our solar system, the Perseus Arm takes its name from the constellation in which it is most prominent, though we also see this structure through Cassiopeia and Auriga, as well as grazing view through the more southerly constellations Monoceros, Puppis, and Vela. From dark sky, the band of silver starlight appears prominent, though not nearly as striking as the northern-summer Milky Way towards Sagittarius and the center of the galaxy. The Perseus Arm appears dimmer because we see fewer stars in this direction than when looking towards the galactic core. In the image at top, made with a DSLR and wide-angle lens, a section of the Perseus Arm appears quite bright, but the same image towards Sagittarius would overexpose the sensor to starlight.

The above image shows a useful schematic of the Milky Way and helps us visualize which spiral arms we see when we look in various directions in the sky. The Perseus Arm begins at the distal end of the large bar at the core of the galaxy, while the Scutum-Centaurus Arm emerges from the proximal end of the bar. We live in a small spur off the less prominent Orion-Cygnus Arm. When we look towards the galactic core, we see the Carina-Sagittarius Arm and, through gaps in the ever-present clouds of dark galactic dust, into sections of Scutum-Centaurus.

Spiral arms are where the action is in the Milky Way. Here we find new star formation, chemical evolution as dying stars create heavier elements that give rise to new solar systems, and plenty of brand new stars blowing holes in the gas cloud from which they emerged. Which is why we see, even with a modest telescope, so many fine deep-sky objects here.

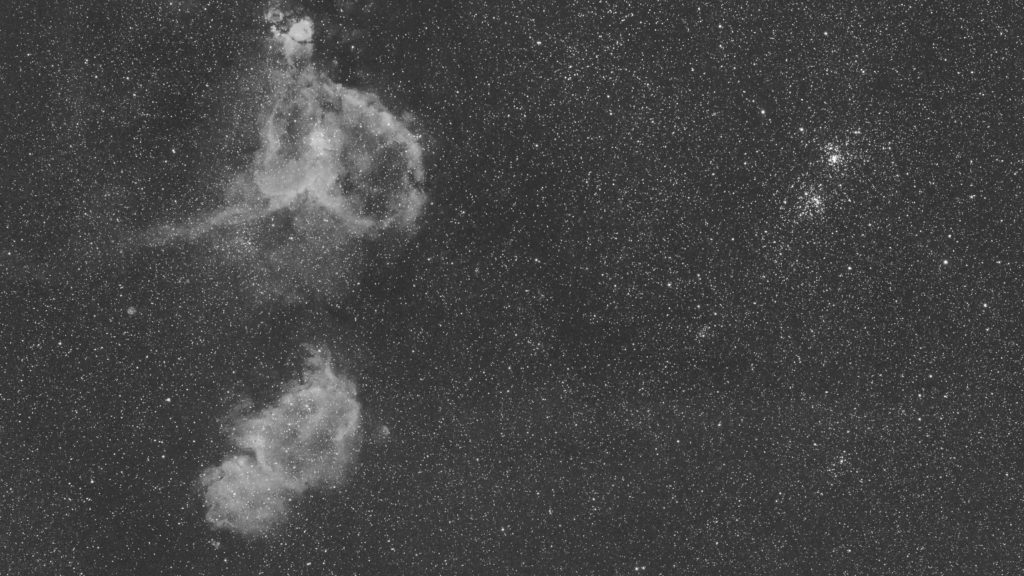

There’s the photogenic Heart and Soul nebulae, IC1805 and IC1848, respectively, a target of many astrophotographers this time of year. The nebulae themselves are just window dressing to the obscured process of star making in this part of the sky. Within the Soul Nebula, for example, lies a strong radio source, called W5, that spans about four full moons and arises from hot stars blasting away gas and dust inside the molecular cloud. Plenty of new blue-white will emerge here in the next few million years.

There are plenty of open star clusters, also, loosely bound groups of new stars that emerge from the remnants of emission nebulae as the star-making fuel runs out. Despite their great distance, these clusters are dazzling in a small scope. A short list of Perseus Arm favorites include M52 (Messier 52), M103, and the lovely NGC7789 in Cassiopeia, and M36, M37, and M38 in Auriga.

And there are many foreground objects here in the direction of the Perseus Arm. That includes the California Nebula (NGC 1499), a 3-degree-long cloud of tenuous hydrogen gas set aglow by the bright blue star Xi Persei. It’s about 1,000 light years away. An extremely difficult object to see visually, it’s a delight for astrophotographers and was first discovered photographically by E.E. Barnard in 1884. The Taurus Molecular Cloud is also a foreground object in this part of the sky.

The best sight for small telescopes is, inarguably, is the famous Double Cluster in Perseus, NGC869 and NGC884. A rare assembly of two separate open clusters stuffed with new stars that just emerged from the star-making machinery of the Perseus Arm about 10 million years ago. These clusters present a magnificent sight in a telescope, spanning a full degree of sky, an impressive apparent size considering the clusters are about 7,500 light years away. Were these clusters the same distance as the Pleiades (about 400 light years) they would span a quarter of our night sky and display hundreds of stars that rival Sirius in brightness.

The finest parts of the Perseus Arm lie overhead during the evening hours in the depths of northern winter, which, depending on where you live, offers chilly to ridiculously cold observing conditions. Some observers worry about their electronics operating in such temperatures; where I live, I’m often more worried about losing body parts to frostbite. To avoid the cold, you can observe the delights of the Perseus Arm while enjoying slightly warmer temperatures of early spring when the stars move to the northwest, or in the late-night hours of autumn the year before as they rise in the northeast. It’s always worth the effort, and there’s always something good to see.

Share This: