Second only to the rings of Saturn, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot (GRS) is probably the most iconic planetary feature in the solar system. Unlike the rings, which aren’t going away any time soon, recent observations of an apparent unraveling of the GRS suggest big changes in this iconic feature, if not its impending demise.

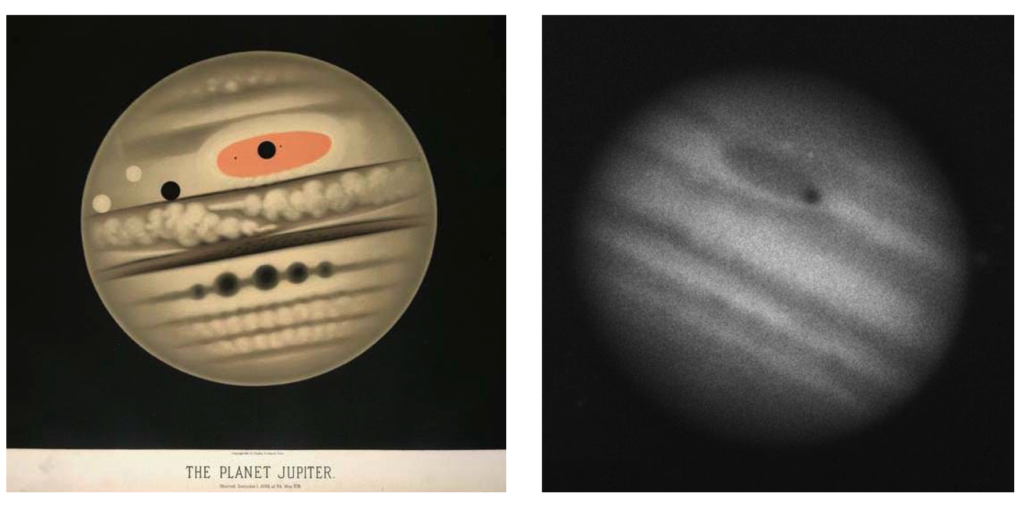

The Great Red Spot is known to have existed since at least 1830 and it has been continuously observed at least since the late 19th century if not before. The multi-talented English scientist Robert Hooke recorded a persistent spot in 1664, but that may have been a different marking than the current GRS. Giovanni Cassini, whose interest in astronomy was more focused than Hooke’s, reported a lasting spot in 1665. It was observed for about fifty years, but then came a long gap in observations that makes it impossible to be sure his spot was the same as the present GRS. In 1711 the Italian painter Donato Creti produced a canvas which includes a depiction of the planet Jupiter. It very much resembles the view through a small telescope today, and it includes something that looks like the Great Red Spot. Creti may have either observed the planet himself or received an accurate description from Eustachio Manfredi, an astronomer who oversaw this and other space-themed paintings made by Creti. These paintings can be seen at the Vatican today. The upshot is that we don’t know how old the GRS really is, but its age must certainly be measured in hundreds of years.

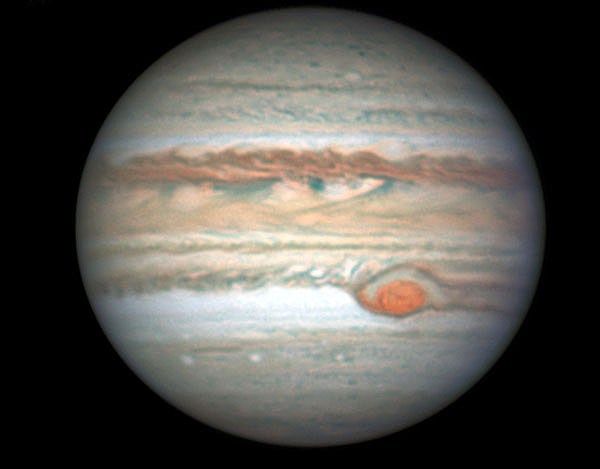

Since then the Spot has waxed and waned, but mostly waned. The first drawings and crude black and white photographs show a much larger, wider Spot than anyone now living has seen. It was seen to be at least 35,000 miles wide in the late 1800s, more than four times the width of the Earth. Even as recently as the 1970s, when I began my own observations of Jupiter, the Spot was at least 50% bigger than it has been in recent years, and deeply colored. It was then prominent in a 3-inch refractor. It can still be seen in such an instrument, but it’s now much less obvious. When the Pioneer space probe buzzed by Jupiter in 1974 it showed us a wide, very red Spot floating almost in isolation in a white Zone, rather than being tangled on the south side of the South Equatorial Belt as it has been more recently. In 1979, the Voyager space probe whipped by on its way to the outer planets, revealing a Great Red Spot a bit more than twice as wide as the Earth.

We’ve seen the GRS gradually dwindle for decades, especially in width. It’s now more nearly circular than the wide oval it used to be. It’s down to roughly the size of the Earth, still pretty great, but no longer overwhelming. Even its color has varied dramatically, for reasons no one clearly understands. The GRS stands above the surrounding clouds, but as it has contracted in area, it has also grown taller. That may have influenced its current vivid orange color, as whatever chemical compounds are responsible for its color are exposed to greater levels of incoming radiation. At other times it has been a deep red color, but has also paled to shades of salmon, light tan, and even to white. It has gone through spells when it was invisible as anything more than a white bay in the South Equatorial Belt, possibly because of an obscuring layer of ammonia clouds.

Now, during the apparition of 2019, something new is happening. The defences that have allowed the Great Red Spot to persist for so long may be breaking down. Like opportunistic looters, the racing winds on the north and south sides of the Spot are unwinding and ripping away its outer parts and blending its colored gasses into the general Jovian atmosphere. Just this year, the GRS has lost between 5-15% of its size. This sudden erosion of the GRS has not been seen before to such a degree. Great “blades”, curved segments of its outer border, are being torn away and dispersed, a phenomenon easily visible to advanced amateur observers and imagers. Why now? Scientists speculate that the Spot’s nearly circular form is less stable that its previous more elongated shape, inviting poaching by neighboring jet streams.

With Jupiter now just past opposition, visible in the sky all night, this is a good time to try for your own glimpse of the GRS’s possible demise. The Spot can be well seen for about a third of Jupiter’s ten-hour rotation period, and these streamers appear to be peeling off about once a week. With persistent observation you have a fair chance of seeing this process for yourself, assuming it continues.

Disintegrating or not, my recent views of the Great Red Spot from the pristine, steady skies of the Grand Canyon still reveals a striking sight, a tangerine oval being licked and nibbled at by the serpentine tendrils of the South Equatorial Belt.

Are we witnessing the final years, or even months, of the Great Red Spot? If it does disintegrate, will it someday rise again, or will a similar storm form at some other latitude? Will one of the existing white or red ovals grow to take the place of the vanished maelstrom? Maybe the Great Red Spot is destined to become a legend of astronomy, something old time observers can brag that they used to see, like dark skies, or skies free of swarms of satellites.

Note: Jupiter is still bright and well positioned for observing in 2019. To learn more about how to get the best of view of the planet, read our Jupiter Observing Guide at this link.

Share This: