When sight-seeing larger nebulae (like the North America Nebula) and big star clusters (like the Double Cluster or Beehive), it’s usually best to stick with lower magnification and wider fields of view to take in the entire object. But most deep sky objects benefit from greater magnification, sometimes much greater. To demonstrate this, I prowled around in the constellation of Hercules, using my 8-inch Celestron Edge HD scope and an 8mm eyepiece, giving a magnification of 250x.

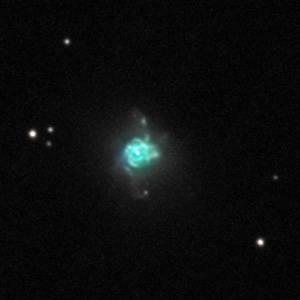

The first object on my tour was the planetary nebula NGC 6210. Like many planetaries, it has a high surface brightness that enables it to bear high magnifications well. At low powers it looks like a tiny bluish dot. 250x brings out considerable visual character in this 16 arc second object. Slightly oval, its edges are diffuse. Colorful as many planetaries are, it shows an aqua tint with hints and flashes of a fierce electric blue. I found that an 8-inch scope isn’t quite big enough to show these colors strongly in this particular object, but a 12-inch or larger instrument will make them unmistakable, and then you’re viewing an exotic object indeed. I did not consistently see the nebula’s central star, though this should not be difficult at magnitude 12.7. This may be due to the consistently rough seeing I experience in this valley of the southern Sierra Nevada range, where I’m surrounded by mountains on all sides. This tends to muddle the faint star into the bright glow of the nebula.

Those bigger scopes I mentioned may also show a faint outer envelope around this object, or maybe even the irregular “legs” that radiate from the main disk, but I saw no sign of them.

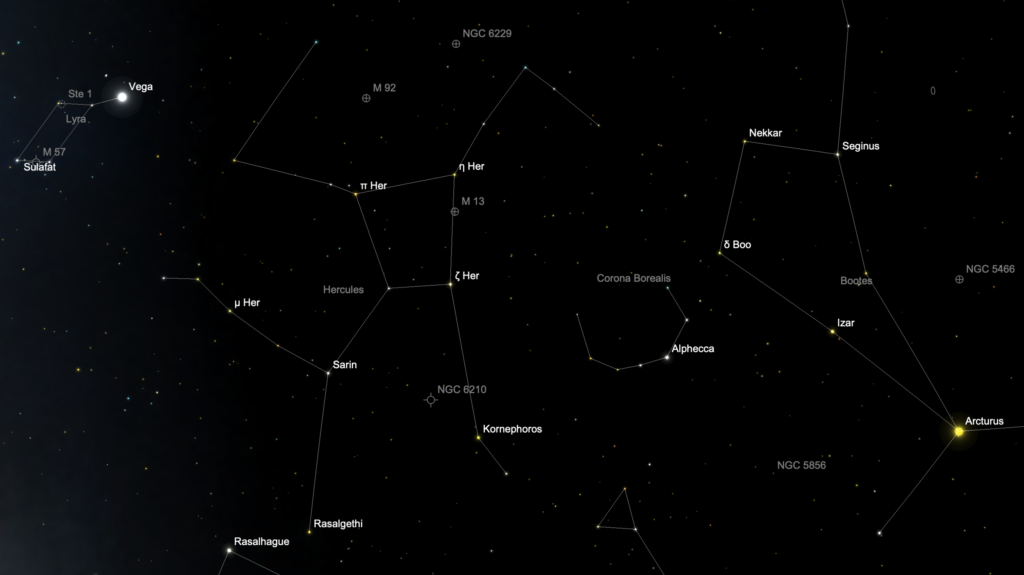

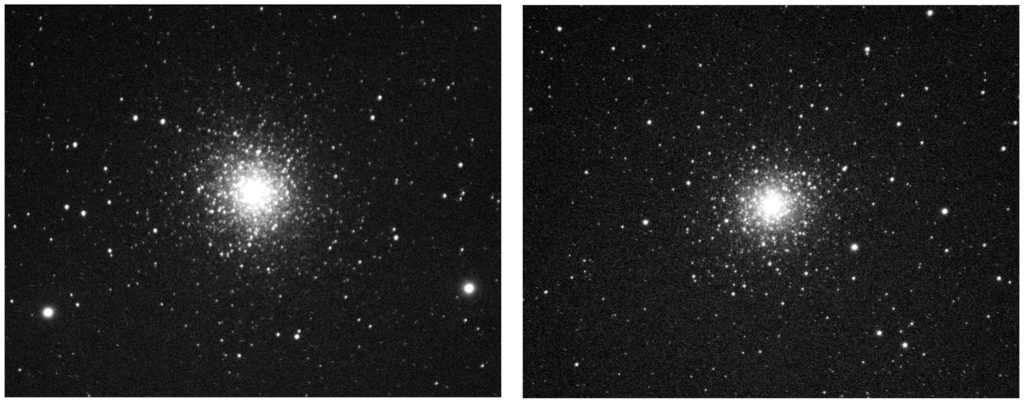

Naturally, anyone observing in Hercules must make a stop at the famous M13, which is generally considered the finest globular cluster in the northern hemisphere of the sky. Low powers show a sparkly ball floating among many foreground stars. Cranking it up to 250x reveals a far more imposing, in-your-face object. Occupying half the field of view, the cluster is clearly resolved right across the center with hundreds of stars. Curved arms of stars branch out into the periphery, giving me the impression of the fins of some species of angelfish (Warning: my visual impressions may not be shared by other rational beings). Observations like these demonstrate the power of a good 8-inch telescope. These high magnifications are likely to be especially helpful under light polluted conditions, where they darken the sky background while leaving the stars of a cluster intact.

Many observers are aware of M13’s “propeller”. This is a three-vaned dark feature with its center offset towards the southeast. The arm that points southeast trails off into the fainter outer regions of the cluster, while the other two, which point north and southwest respectively, are a bit easier to see. None of it crosses over the bright inner core of the cluster. An 8-inch telescope is on the small side for viewing the propeller, but once I thought about it, I saw it easily enough. The vanes or blades are narrow and not exactly pitch black. The whole thing is larger than you might expect.

The physical nature of the propeller is uncertain. The most likely explanation seems to be that it is not actually an obscuring dust feature, but rather attributed to “low stellar column density”, which is essentially a depth of the cluster with a lesser density of stars. Understanding why such a random phenomenon should take the form of a neat three-bladed propeller is well beyond my pay grade.

I consider the ability to resolve at least a few globular clusters a necessary feature of any good deep-sky telescope. Some are easier to resolve than M13, (M4 and M22 come to mind), but what does it take to change M13 from a round mist to a cluster of stars? My 92mm Stowaway refractor will resolve it reasonably well from a dark location. Even a decent 3-inch achromat will give at least a suggestion of resolution. The trick is to use substantial magnification to darken the sky background and separate the stars. For a 3-inch, I suggest about 150x.

An obscure neighbor of M13 is the small galaxy NGC 6207. Many observers take a peek at it when in the vicinity, just to make sure they can see it and to reassure themselves that their telescopes are awesome. It’s not really all that faint at magnitude 11.3. At the usual magnifications it’s just a small, elongated fleck of light. At 250x it takes on new character. The flattened oval disk is clearly visible, as is a definite starlike nucleus.

Well north of M13 lies M92, a globular cluster which would be a popular target in most other constellations, but which pales in the shade of M13. It’s still well worth visiting. My 8-inch scope at 250x resolves it thoroughly in my Bortle 3 skies. It’s about one third the size of M13. Outlying stars spread particularly far to the northeast and southwest. These gave me the impression of butterfly wings, another fanciful view for which I take no responsibility.

Descending a few rungs on the ladder of globular cluster conspicuousness, we find NGC 6229. My 8-inch scope at 250x reveals a misty round glow with a steady increase in brightness toward the core. This 8th magnitude object is easy to see, but offers only fleeting suggestions of any resolution. It looks about the way M13 appears in a 50mm or 60mm refractor. If such a small refractor is all you have, look at M13 and dream of the day when you can make NGC 6229 look like that in the big 8-inch scope you hope to own someday.

Finally we zip down to the southern reaches of Hercules, which actually represent his head, rendering him upside down as seen from the Northern Hemisphere. There we find Alpha Herculis, which, contrary to the usual convention used to assign Greek letter designations to stars, is not the brightest star in Hercules, but may be the most interesting. Also known as Rasalgethi (Head of the Kneeler), this is one of the best double stars in the sky. With a fairly close separation of 4.3 arc seconds, 250x is not an excessive magnification for this object. The pair, which shines at magnitudes 3 and 5, shows the Albireo-like colors of golden orange and pale blue, respectively. This makes sense for the Class M primary star, but the components of the spectroscopic binary pair that together make up the B star are both white G-type stars. The apparent blue color of the B star must therefore be a contrast effect with the golden primary. My 92mm refractor presents this pair beautifully at 120x. As is often the case, a small refractor shows stars as tighter, neater points than a larger reflector, especially in conditions of iffy seeing.

Except for a few other double stars, this has been a survey of all the most prominent deep-sky objects lying within the boundaries of Hercules. It’s a small selection, but when one of them is perhaps the most viewed deep-sky object in the summer sky, you’re doing all right.

Share This: