Sometime in 1955, Mr. David Coffeen of New Orleans, Louisiana came up with $75. In today’s currency, that’s about $700, a respectable sum. And what did Mr. Coffeen do with his hard-earned savings?

He purchased a telescope.

Which telescope? A Unitron altazimuth refractor with an aperture of just 40mm, less than that of most finder scopes today. It came with three eyepieces, a star diagonal, and a wooden storage case, because it was an honest astronomical instrument.

Mr. Coffeen used his telescope from atop his modest trailer home. There was a lot to see with that 40mm scope: loads of lunar detail, the rings of Saturn, the Galilean moons of Jupiter and a couple of belts, hundreds of double stars, many of the Messier objects, and a lot more.

He was so proud and pleased that he wrote to Unitron to show off this arrangement, and became immortalized in the image below:

David Coffeen, I salute you. I’d like to think that in later years you were able to get your hands on a big 60mm scope, or maybe even a massive 3-incher, which would have been considered an impressive instrument!

Today, most amateur astronomers would scoff at the idea of a 40mm telescope, especially as a main (or only) instrument. Some will assure you that an 8-inch (200mm) is a “starter” telescope, and that really, nothing smaller than a 10-inch (250mm) is worth looking through.

The fact is, spending $700 today will get you a decent 10-inch reflector telescope on a Dobsonian altazimuth mount. Even if you insist on a refractor, which is an inherently more expensive breed of telescope, it will still get you a fair 120mm achromatic refractor on a usable equatorial mount, with enough left over for another eyepiece or two. Either is, of course, far more capable than any 40mm telescope.

But don’t count out those tiny telescopes. Few of us started out with anything smaller than a 60mm refractor. That’s about 10 times the aperture of the fully dilated human eyeball (depending on age and other factors). To get that same huge jump in light grasp again, someone with a 60mm scope would need to acquire a 600mm (24-inch) scope. Even today, amateur telescopes of that size or greater are not that common.

What about resolution? The smallest thing the unaided human eye can distinguish as anything other than a point of light is about 2 arc minutes across (theoretically, a 6mm telescope could resolve down to about 20 arc seconds, but our eyeballs are not optically equal to the task). A good 60mm scope will resolve to 2 arc seconds, a 60-fold improvement! To improve this by another factor of 60, you’d need a 4-meter telescope, like the Mayall reflector at Kitt Peak, and it would have to either be in space or equipped with advanced adaptive optics to overcome the seeing limitations of our turbulent atmosphere, which make it uncommon for any telescope to resolve below one half second of arc, no matter how big it is.

The point is this. For most amateur astronomers, that first decent telescope, no matter how small or humble it may be, is by far the biggest gain in observing capability they will ever see, no matter what bigger telescopes they get in the future.

If some people consider a 10-inch scope a starter instrument today, it’s worth remembering that 50 years ago, a 10-inch was about as big a telescope as many amateur astronomers would ever see, let alone own. An 8-inch Newtonian was a hallowed object worthy of reverence, a truly serious telescope, and for that matter, so was a wee 3-inch refractor. To judge from the Unitron advertising of the day, a towering 4-inch refractor was really all an amateur observer needed to aspire to. Unitron claimed that a professional astronomer once said that “a 3-inch refractor will show everything that an amateur would wish to see.” Well, maybe not, but they will provide decent views of at least a few examples of every major class of astronomical object.

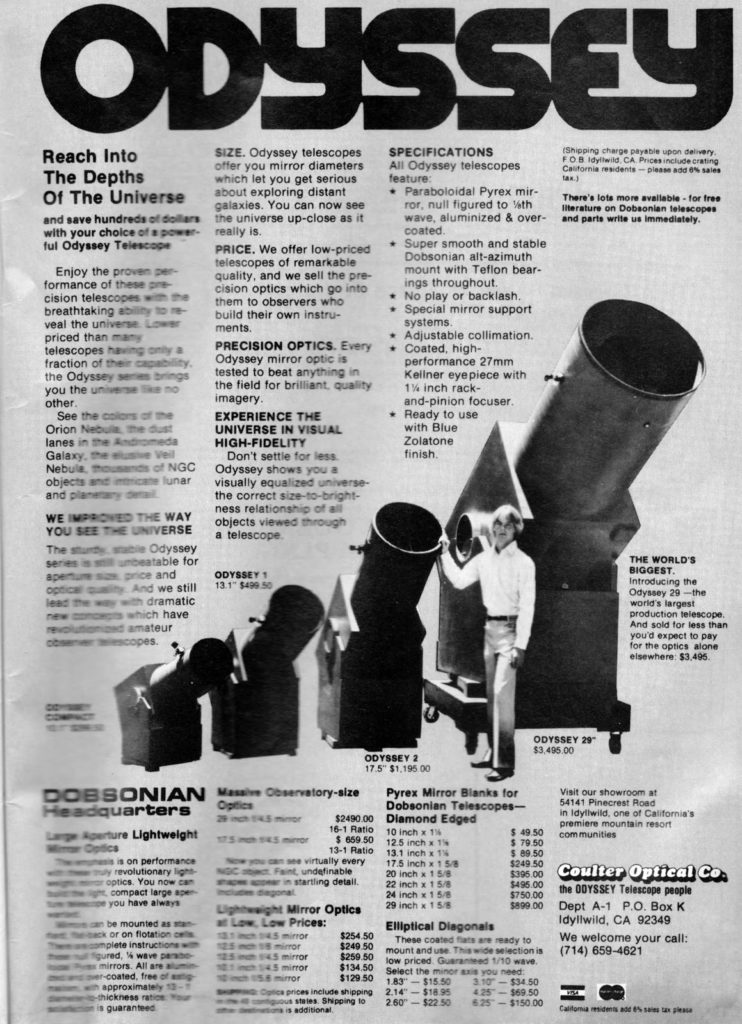

Then in the 1980s, along came the erstwhile monk and astronomy evangelizer John Dobson, who slapped large if optically dubious mirrors into slapdash altazimuth mounts. Telescope makers followed his lead, and suddenly starlight was pouring into our eyepieces! After a few years a 10-inch was a medium-sized telescope, and a 15-inch was the beginning of large apertures. The images in these early Dobsonian reflectors might not have been very refined, but they sure were bright, permitting glimpses into previously unthinkable deep sky depths.

Dobsonians gradually got more sophisticated, their optics improved, and a typical amateur can now get a workable telescope of large aperture that would have been the belle of the ball and featured in Sky & Telescope when he was a kid.

And yet, a fine small telescope remains a treasure, and a thing of wonder. It can be carried around and set up easily. It can be transported without needing a big vehicle or towing a trailer. And it can show you so much. The smallest telescope I regularly use is a short 92mm apochromatic refractor. If it was the only telescope I could own and use, I would still consider myself blessed and in touch with the sky. It provides views of planets that are better than those of many bigger telescopes of other types, it’s spectacular for low-power Milky Way scanning, and when used carefully beneath a dark sky, it can show you a lifetime’s worth of deep sky objects. For example, from the Mojave Desert I easily saw NGC 2419, the “Intergalactic Wanderer”, a globular cluster in the constellation Lynx that lies at the astounding distance of some 300,000 light years. The faintest star I glimpsed in its vicinity was a faint magnitude 13.9.

Modern small telescopes are smaller than ever, or at least shorter. The old ones were achromats (color free) with a focal ratio of f/11-f/16, a necessity to limit residual chromatic aberration, or “false color” from the main lens. Today, the advent of newer glass types makes it practical and economical to make small apochromatic (really, really color free) refractors of short focal length. These highly refined instruments are not only fine for visual use, but they’re also ideal for astrophotography, or imaging, because of their “fast” focal ratios of f/6 or f/7 and their small size that makes it feasible to use them on small mounts.

Big or small, humble or exotic, every decent astronomical telescope shares a few important qualities. One is their purity of purpose. They carry no violence, no greed, no aggression, no anger. They exist only to expand the mind and heart. They provide knowledge, and hint at truth. They are fundamentally simple things, yet precise, and perfectly adapted for their function.

No man-made object is more pure or venerable than a fine old telescope that has been gathering starlight for years or decades. This is as true of a small refractor used to contemplate the Moon from an urban balcony as it is for a big reflector hunting galaxy clusters beneath the darkest skies. If you have either or both, you are fortunate.

Share This: