“It is nightfall; the clouds have vanished,

The sky is clear, pure, and cold…

Silently I watch the River of Stars…

Tonight I must enjoy life to the full,

For if I do not, next month, next year,

Who can know where I shall be?”

– Su T’ung-Po

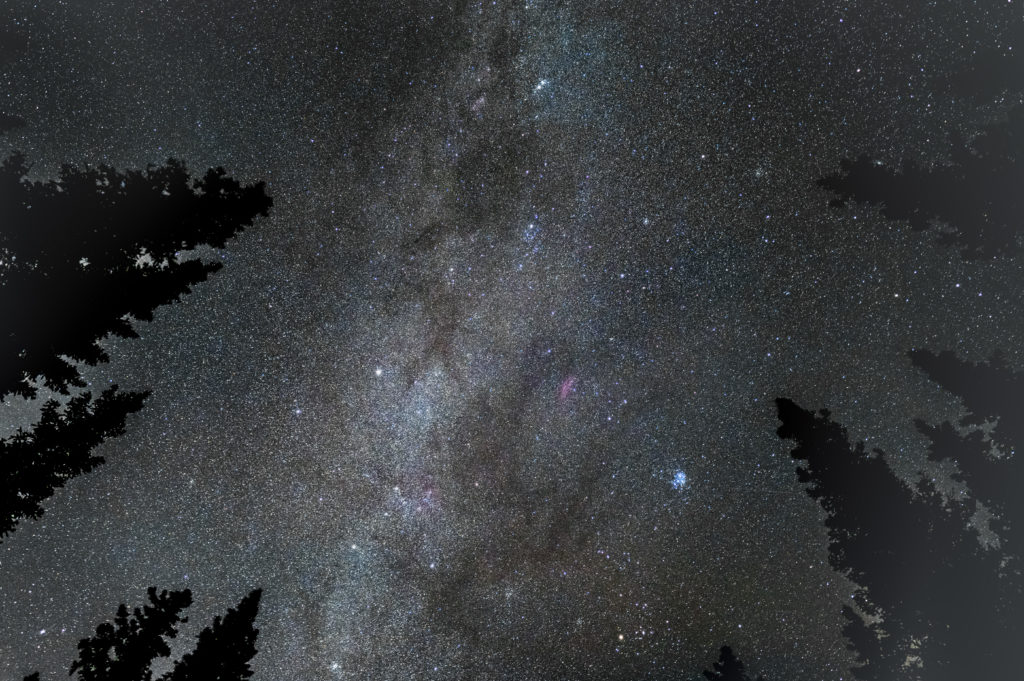

A layer of fresh snow blankets the northern prairie, thin enough for the tops of golden wheat stubble to poke through, while a blast of arctic air from the northwest sweeps the darkening sky clean. Driving south on a secondary highway, an hour east of the city, I turn onto a back road and pull over by the side in complete darkness save for the lights of a farmhouse half a mile away. Emerging into the cold, I exhale a frosty breath and gaze upward into a bowl of black sky full of crackling stars. To the west I see Pegasus plunging towards the horizon with Andromeda in tow. The Big Dipper lies low in the north, its handle grazing the flat landscape and bowl pointed to the upper right. But the best view tonight lies overhead along the pale arc of the northern Milky Way through the bright constellations Perseus and Auriga, and down to the east skirting Orion’s eastern shoulder, passing the feet of the twins of Gemini, and into Canis Major, the Big Dog, with Sirius hovering over a snow-covered spruce tree like a Christmas star. As my eyes grow adapted to the dark, the outlines of our home galaxy begin to emerge. I grab my little telescope from the back of the car, set it securely on its mount, and get to work.

To us stargazers, the term ‘Milky Way’ refers to the pale white, hazy band of unresolved stars that encircles the sky and wheels into view mostly during the summer and winter months. Nearly all cultures have a name for it. Chinese and many Asian sky watchers called it the “Silver River” or “Star River”. The Spanish called it compostela, the “Field of Stars”. Norwegians called it Vinterbrauta, the Winter Way, since its brightest regions visible in summer are obscured by perpetual twilight of high northern latitudes. Perhaps most evocatively, the !Kung bushmen of southern Africa, who had a spectacular view of its thickest expanse, called it the “Backbone of the Night”.

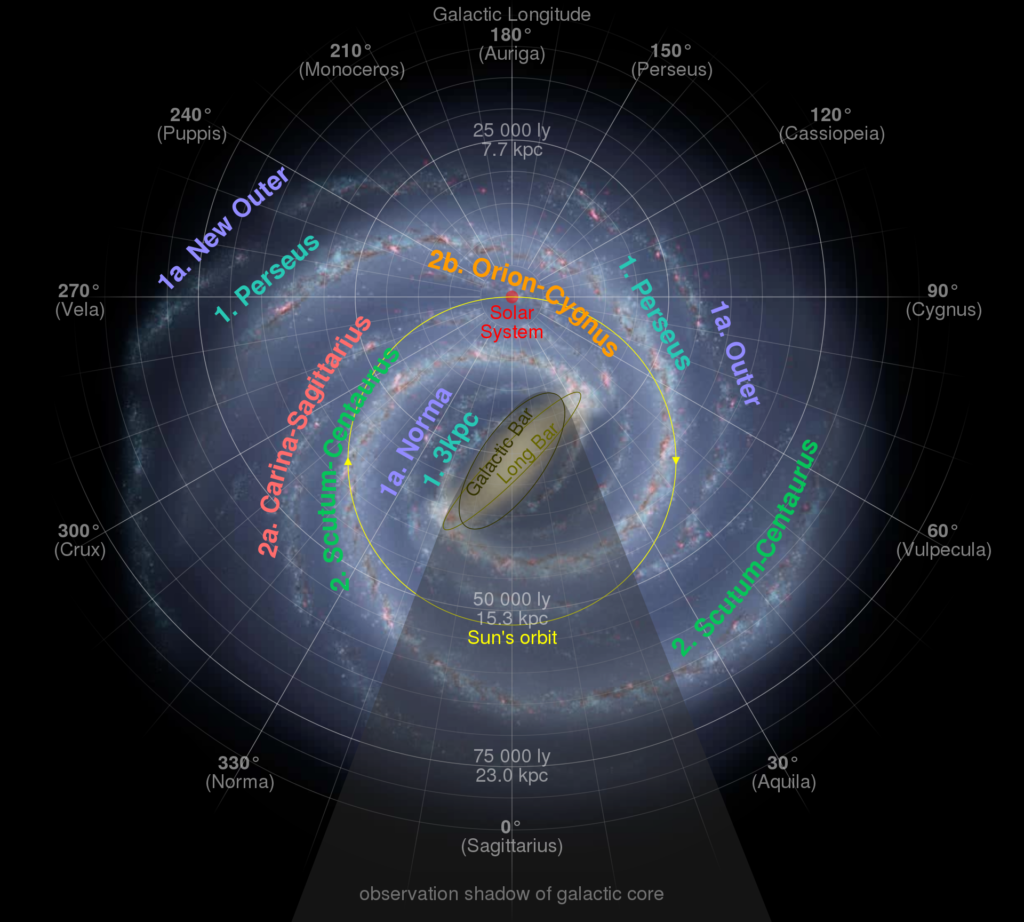

All the stars along the band of the ‘Milky Way’ belong to our home galaxy which, confusingly, is also called the Milky Way. As galaxies go, it’s a beauty. A larger than average spiral galaxy, it features a bright central bulge and bar from which two large flocculent spiral arms emerge and wind around in a flat disk. These arms, and a handful of smaller spiral arms and spurs, contain most of the gas and dust that serves to form new generations of stars. In its current form, the starriest part of the entire Milky Way galaxy spans about 100,000 light years but has a thickness of just 1,000 light years. Freshly-minted blue-white stars pack the thin pinwheel-shaped disk while a spherical central bulge contains far older yellow-white stars, giving the galaxy a layout rather like a large dinner plate with a dollop of buttery mashed potatoes in the middle.

Despite its size and evident grandeur, the Milky Way emerged from humble beginnings not long after the the birth of the universe about 13.7 billion years ago. It may have started with clumps of hydrogen and helium gas and still-mysterious dark matter a few hundred million years afterwards. Within this clump formed some of the first stars, which ended as dense black holes, which in turn served as a gravitational flytrap to draw in more primordial interstellar gas, stars, and smaller galaxies over the next few billion years. Its inherent rotation eventually flattened into its current disk-like shape that revolves around a now-immense black hole at its center. Even today, the long gravitational arm of the galaxy assimilates stray clouds of cold gas, rogue stars, and dwarf galaxies from its local neighborhood. The Milky Way is not so much a single fixed thing but a dynamic process, a self-assembled celestial empire that’s grown over billions of years to a population of some 200-400 billion stars.

From our vantage point, about 25,000 light years from the center of the galaxy, we mostly see only a fraction of the Milky Way galaxy out to a radius of about 5,000 light years. Obscuring clouds of dark interstellar dust obscure the rest of the galaxy from our view, at least at visible wavelengths. In the northern summer, we look towards the galactic into the spectacular starry band of one of its two major spiral arms, the Scutm-Centaurus Arm and the smaller Carina-Sagittarius Arm. They take their names from the constellations in which they appear prominent. On this northern winter night, I’m looking away from the center into the thickest part of another major spiral arm, the Perseus Arm. In this part of the sky, I’m looking almost exactly opposite the galactic center so the view is more subdued compared to the summer Milky Way, but there’s still plenty to see.

My little telescope, about half the length of a baseball bat and twice as thick, is solid as a craftsman’s tool. While tiny by the standard of professional astronomers, it collects about two hundred times as much light as the human eye and offers a relatively expansive view of the sky about as wide as three fingers held at arm’s length. I indulge myself by aimlessly sweeping the rich star fields of the Perseus Arm and stopping to see a few favorites. I start in star-speckled Cassiopeia, pausing to consider Rho Cass, a yellow-white hypergiant that’s among the largest stars in the galaxy. I move on to clusters of relatively new stars including the sparse NGC 457 with two eyes and outstretched arm that resembles the movie alien ‘E.T’, and the Y-shaped Messier 103. I hop the border into the constellation Perseus to see the magnificent Double Cluster – a stunning piece of celestial jewellery with no equal in the sky. Located some 7,500 light years away, these twin star clusters formed about 12 million years ago out of cold gas and dust in the Perseus Arm. Were they as close as the Pleiades, these two clusters would span nearly a quarter of the northern sky and many of its 600 stars would shine as bright as Sirius. Then I sweep onward to more stars, and more stars, then into Auriga to linger on the trio of open clusters Messier 36 and 38, and especially M37, a densely packed open cluster with an age of 350 million years which makes it an elderly denizen of the Perseus Arm.

I’m not doing any science here, nor am I taking images or sketching, nor doing much of anything other than looking. I’m looking with full attention at the handiwork of a galaxy that, with the help of gravity, turns dark clouds of cold hydrogen gas made at the beginning of the universe into clusters of spanking new stars. It’s a staggering sight. While distant and faint, these star clusters and clouds and nebulae are not indistinct facsimiles, drawings, artist rendition, they are the real thing, products of a major galaxy in action. Yet it’s at least partially accessible to anyone who cares to look with a little practice and less effort than it takes to sweep snow off the front walk.

As I sweep the scope further southeast, the Perseus Arm recedes and turns a corner and the intervening and much closer Orion-Cygnus Arm comes into view. Also called the Local Arm, this minor spiral arm harbors our own solar system on its inner edge. Most of the bright stars visible to the unaided eye in this part of the sky belong to it although some, including our Sun, are just passing through. At the feet of Gemini I encounter more sprawling star clusters resident in the Orion Arm. There’s Messier 35, which resembles a tiny sugar donut. Then about twelve degrees east of Sirius I see the sparse Messier 47 in the constellation Puppis and the adjacent and far richer Messier 46, which also harbors a tiny ring-like planetary nebula ejected from a dying mid-sized star. All these jewel-like star clusters are interesting not for what they look like but for what they are: immense families of newly formed stars.

Surprisingly, the crown jewels of the northern winter sky do not lie along the Milky Way but slightly adjacent to it in the constellation Orion, the Hunter. Perhaps the most recognizable constellation, Orion presents a majestic sight as he rises above the southeastern horizon in early winter, his shield facing the fierce celestial bull of Taurus and a spangled sword hanging from his prominent tri-starred belt. The Milky Way runs past his eastern shoulder marked by the brilliant red supergiant star Betelegeuse. Blue-white Rigel marks his western foot. Plenty of star clusters and nebulous stellar nurseries fleck Orion along with coal-black clouds of coal molecules and interstellar dust that are slowly collapsing into even more star-forming regions. As we will see, the activity in Orion was triggered not by the usual gravitational tugging and kneading inside a spiral arm of the galaxy, but possibly because of a collision between the Milky Way and an external intergalactic cloud that formed an undulating wave of compressed gas and dust that spans half the sky.

After it skirts Orion and passes through Canis Major, the winter Milky Way continues below my local horizon into the constellations Vela (the Sail) and Carina (the Keel), which along with Puppis (the Stern) in antiquity comprised a single immense constellation called Argo Navis. Here, and further south into Crux or the ‘Southern Cross’, the Milky Way becomes truly spectacular for observers south of the equator. Many northern stargazers dream of heading south to see this most spectacular section of sky, and all who go agree it’s worth the trip to see the ‘other half’ of the galaxy.

Thoughts of a warm night stargazing in the southern hemisphere distract me now as the heat drains from my body, despite wearing extra layer clothing, after standing nearly still over a telescope for an hour in the icy night. So I pack up the telescope and prepare to head home. Before leaving, I set up a camera and a wide-angle lens to capture a few images of Orion and the winter Milky Way running off its eastern shoulder down to the horizon. Serious astrophotography involves gazing at computer screens more than the stars, which is not for me, but I sometimes snap a few photos to remember the night. I’ve taken dozens of photos of this part of the sky, all similar but no two exactly alike, and I’ve seen it hundreds of times since I first started serious stargazing well before my tenth birthday. It never grows tiresome. These stars change little over a brief human lifetime, but new discoveries about the Milky Way and my own efforts to better understand what’s out there and how it fits together lets me see it slightly differently each time. To paraphrase Heraclitus, no man ever steps in the same star river twice.

Share This: