As northern summer nights grow longer in August and September, the big constellation Cygnus lies nearly overhead before midnight and offers dozens of colorful nebulae and star clusters for visual observers and astrophotographers. The newly discovered Radcliffe Wave begins here. So does the dark and dusty Great Rift that splits the band of Milky Way in two. Cygnus also contains the brightest section of the northern Milky Way in the grand Cygnus Star Cloud, the most prominent star cloud north of the celestial equator. With a pair of low-power binoculars or with just your dark-adapted eyes, this billowing collection of millions of stars along an arm of our galaxy offers as beautiful a sight as any earthly work of art or nature.

While astronomers have precise definitions for open and globular star clusters, there’s no physical definition of a star cloud. These formations of unassociated stars get their name from their passing similarity to earthly cumulus clouds and simply appear as prominent condensations of stars along the band of the Milky Way where obscuring dust and gas let light from more distant stars shine through. The Small and Large Sagittarius star clouds and the Scutum star clouds are the most conspicuous examples, and there are many more. On a trip to the southern hemisphere earlier this year, I staggered back in slack-jawed amazement at the sight of the Sagittarius star clouds rising in the pristine desert air. The Cygnus star cloud isn’t that bright, but it’s large and prominent enough to make it worthy of careful and unhurried inspection.

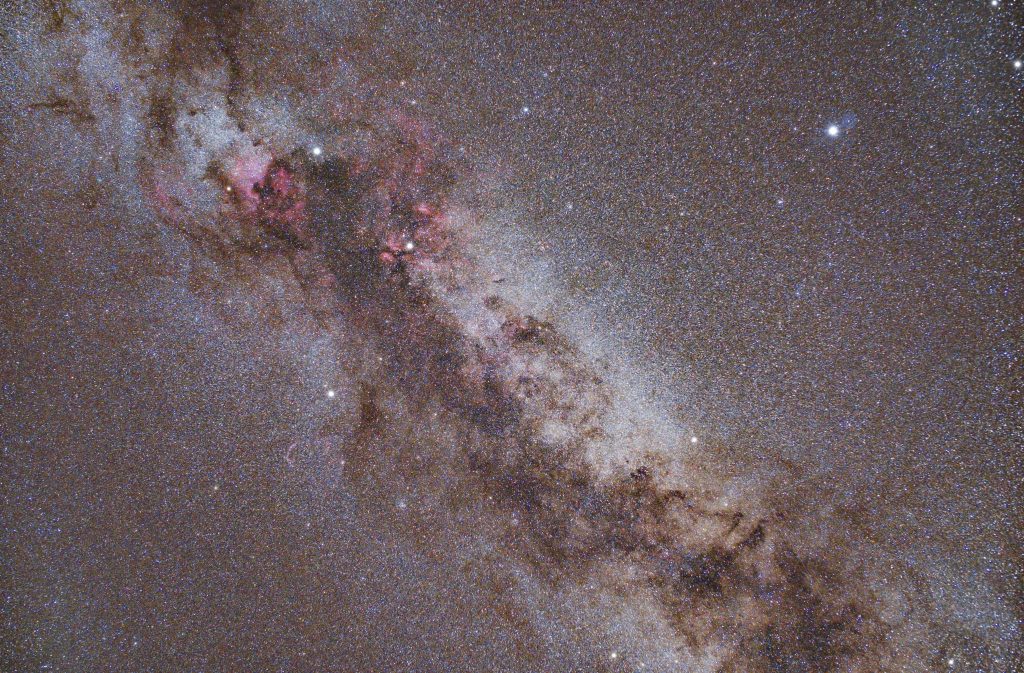

You can see the Cygnus star cloud as a large elliptical glow about 16o on its long axis running southwest to northeast between the stars Sadr (γ Cygni) and Albireo (β Cygni). In dark and moonless sky, the cloud appears easily to the unaided (and dark adapted) eye. It’s too large to fit into the field of view of most binoculars, although a pair of wide-field ‘constellation’ binoculars can fit the entire vista. The southeastern edge of the Cygnus star cloud ends at the dark and dusty ‘Great Rift’ which runs parallel to the cloud but extends down the length of the northern Milky Way.

Near Albireo, the cloud appears as an ill-defined but quite splendid starry field in 10×50 binoculars. Larger apertures resolve the cloud into a grainy haze. The views become more interesting along the edges of the star cloud along the Great Rift, especially near the star η Cygni which lies about halfway between Albireo and Sadr. Here you can see all manner of interesting patches of stars terminated by dark lanes that penetrate the edge of the star cloud. In a telescope at low magnification, the northeastern edge of the cloud near Sadr looks particularly interesting with channels of darkness creeping into the cloud along with the ghostly glow of the Butterfly Nebula (IC 1318). Near the middle of the cloud lies the intervening dark dust cloud B144 which appears simply as a slight dearth of stars in an otherwise rich field. You can see the dark nebula in the middle of the cloud at the image at top.

The Cygnus star cloud is a destination itself. Not many deep-sky sights lie within its perimeter, but a few objects of interest lie around its periphery. They’re not related to the cloud itself, but make for good stops on a telescopic tour of the area. These sights include:

- IC 1318, the Butterfly Nebula, a bifurcated oval of light superimposed on a rich star field. Responds well to a nebula filter.

- M29. A tiny but strangely appealing little open cluster with 8-10 bright stars that looks like two brackets placed back-to-back “)(” about 7’ across.

- NGC 6910. A Y-shaped cluster, about the same size as M29, just east of Sadr.

- NGC 6888. The famous Crescent Nebula formed by energetic outflows from a Wolf-Rayet star. This one needs some aperture, at least 100 mm, to spot in dark sky.

- NGC 6819. An attractive 7th-magnitude open star cluster on the northwester edge of the cloud. With a couple of dozen dim stars that span about 13’, this one resolves well in a 10” reflector. Easier to see than the globular star cluster M56 in Lyra, which begs the question of how Charles Messier missed this underappreciated gem.

- NGC 6871. A loose collection of stars on the southeastern edge of the cloud, this 5th magnitude cluster spans about 30’. Easier to see than NGC 6819, but not as pretty.

And of course, don’t forget to visit Albireo (Beta Cygni) at the southwestern tip of the Cygnus star cloud. This blue-white and gold pair, spaced by a generous 35”, splits nicely in any telescope and many binoculars, and, like the Cygnus star cloud itself, never grows tiresome.

Share This: