In my previous sky tour, I talked up the virtues of observing deep sky objects using fairly high magnifications with a reasonably big 8-inch f/10 telescope. This time around, let’s veer to the opposite extreme and take a tour of a series of celestial objects that are best seen using small telescopes, low magnifications, and wide fields of view.

Cygnus, the Swan, which is as emblematic of northern-hemisphere summer as any other constellation, holds two of the best examples of wide-field objects which are visible nearly overhead in late northern summer, and low over the northern horizon for southern-hemisphere observers.

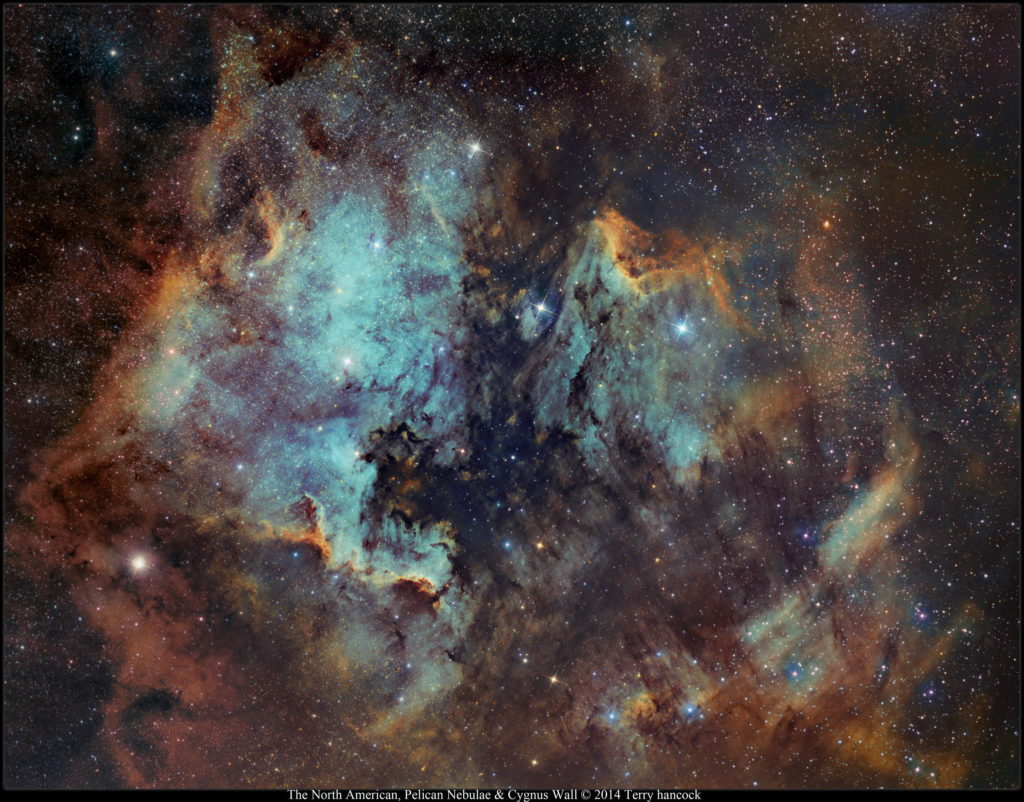

The North America Nebula

The first is the iconic NGC 7000, the North America Nebula, which is easy to find just northeast of the bright star Deneb.

Using my 92mm f/6.75 refractor at 18x with a 35mm Panoptic eyepiece, I get an expansive 3.8o field. This is needed to show the sprawling North America Nebula in its entirely, and it frames it beautifully. Beneath my dark Bortle 3 desert sky, the nebula is visible in an unfiltered view, half lost among the throng of Milky Way stars in this area. An Ultra High Contrast (UHC) filter greatly improves the view, even with these dark skies. The shape of the nebula, which echoes Earth geography so well, can be clearly seen.

The striking shape of the nebula is created by intervening clouds of dark dust which hide some of the glowing nebulosity that lies beyond them. The most obvious example is the round, dark blob that creates the nebula’s “Gulf of Mexico”. Without these obscuring dark nebulae, the bright nebula would reveal an altogether different shape and appearance. Maybe it would look like some other continent. Who knows?

Keep in mind that the image you see in your eyepiece may be inverted, unless you’re using a refractor or Cassegrain telescope with a star diagonal, in which case it will be right side up, but still flipped right to left. This may briefly confuse your perception of the continental character of this nebula.

The brightest and best defined areas of the nebula are Central America, Mexico, the Gulf Coast, and Florida. As you move farther north, both in the sky and according to the layout of the nebula, it gradually fades into the thick starry background as you approach the rapidly thawing ‘Arctic’.

Lying off the East Coast of the North America Nebula is perhaps the biggest and most monstrous Kaiju of all, a colossal Pelican. These nebulae are cataloged as IC 5070 and IC 5067, and are collectively called the Pelican Nebula. It too can be seen with the aid of a UHC filter, albeit faintly, but its complex shape is hard to make out. A fairly prominent unequal pair of stars in this area could represent the Pelican’s eyes, if they could just be nudged over a little bit. This object is much less obvious than the North America Nebula, so don’t berate yourself if you don’t see it. Of course they are all part of the same nebular complex, separated only by those intervening clouds of dark dust.

The Cygnus Loop

Just off the east wing of the flying Swan lies the faint naked eye star 52 Cygni. This marks the spot of the fabulous Veil Nebula complex. Also known as the Cygnus Loop, here we find a few separate objects, many with their own NGC designations, which are all part of the same thing, the expanding remnant of a giant star which exploded as a supernova roughly five to eight thousand years ago.

With its 3.8o field, my little refractor encompasses the entire Loop with not much room to spare. Again, a UHC or Oxygen III (OIII) filter makes it much easier to see, and it may be a necessity under poorer skies. The two most obvious sections are NGC 6960, known as the Western Veil, the part which apparently runs through the star 52 Cygni, and the opposing Eastern Veil, NGC 6992. Of the two, the arc of 6992 is significantly brighter and easier to see. The “glare” of 4th magnitude 52 Cygni helps make the 6960 section less conspicuous.

About a degree northeast of 52 Cygni, you may faintly see the section known as Pickering’s Triangular Wisp. This bit was actually discovered by a woman named Williamina Fleming, but somehow it came to be named after the man she worked for at Harvard College Observatory, Edward Charles Pickering. Funny how things like that happen. Like the Pelican, you may have trouble making out the actual shape of the Wisp, but you have a good chance of seeing there’s something there.

While the Veil is a case where a very low power is needed to see the entire object in one view, adding magnification, and especially aperture, vastly improves the appearance of its individual parts. Going to 28x with my 92mm scope adds significant detail to the Eastern Veil, and shows the forked, hook-like structure on its southern end. But in this case, there is truly no substitute for aperture. A 10-inch scope and a medium power turns both of the Veil’s main arcs into twisted skeins of filamentary detail. If you ever have a chance to view the Veil in a really big amateur scope, say 15 inches and above, you’ll see one of the most wondrous things in the sky, a bewildering array of threads of light, exactly as you’d see them in a photograph, but dimmer and without color.

To me, the most impressive of these features is the “Tornado”, a curved, sharp-edged saber of light that pokes out to the north from 52 Cygni. It’s considered a “rolling vortex”, a rotating structure of glowing gas. The remnants of the exploded star slam into the thin substance of the interstellar medium at 170km/second. The Tornado feature is visible in small telescope, but a big one will show you the weird glow of the thin lines that define the edges of this cosmic whirlwind.

Remember, the Veil is still expanding! Try to observe it within the next thousand years or so. Otherwise it might get too big to be seen as a whole in any reasonable telescope.

Share This: