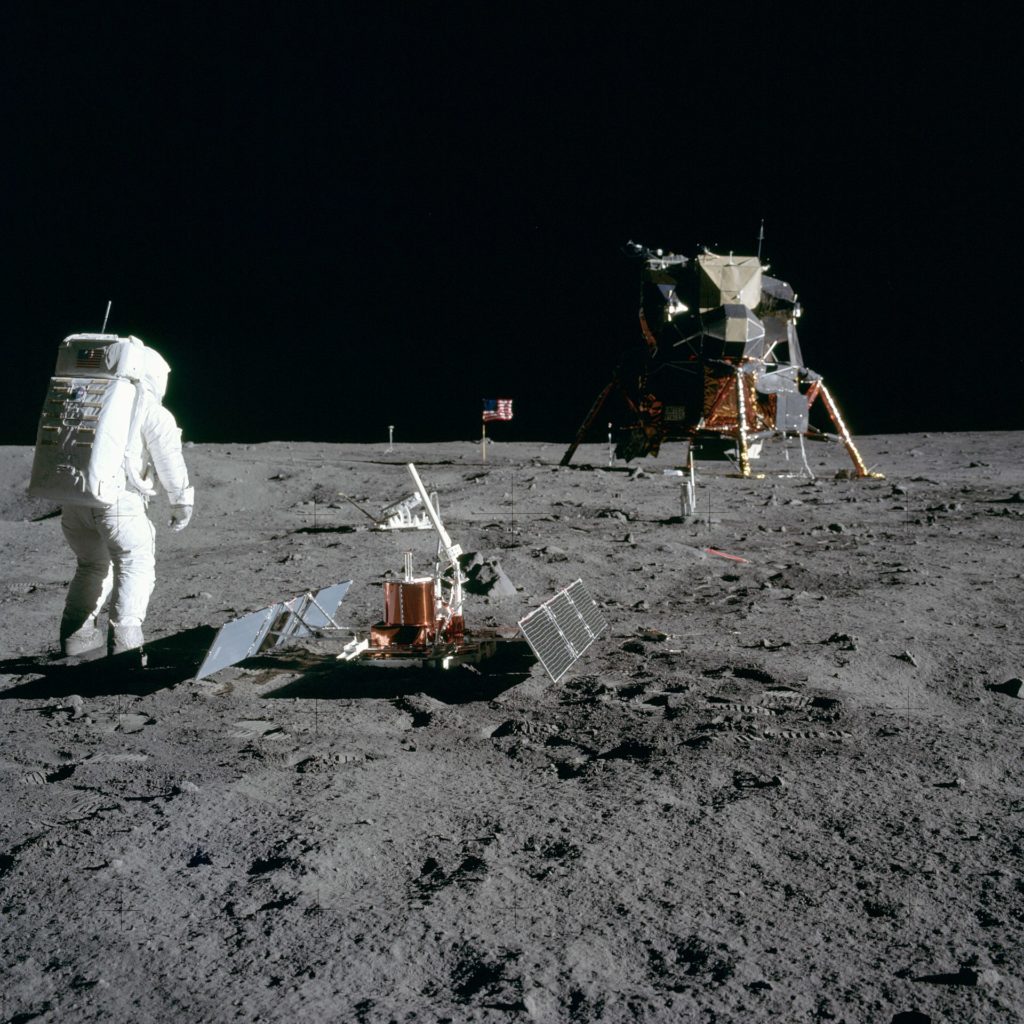

As the world celebrates the 50th anniversary of the still astonishing Apollo 11 moon landing, we backyard stargazers can also get in on the fun (indeed many of us grizzled amateur astronomers can trace our interest in the night sky to the space program of the 1960s). With a modest telescope and good seeing, nearly anyone with a little observing experience can see the region of the Moon where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin briefly walked, and observe the three tiny craters named for the two famous moonwalkers and their crew mate Michael Collins who remained alone in lunar orbit to pilot the Apollo 11 command module.

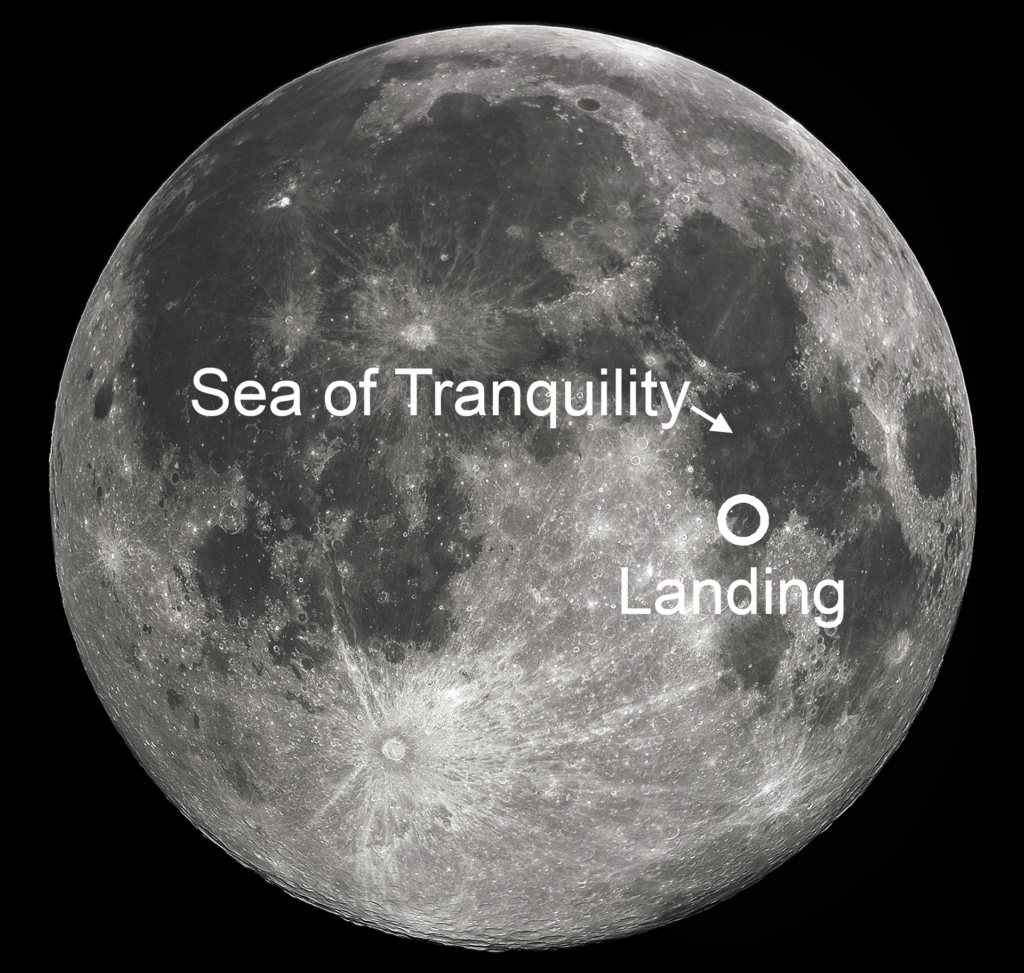

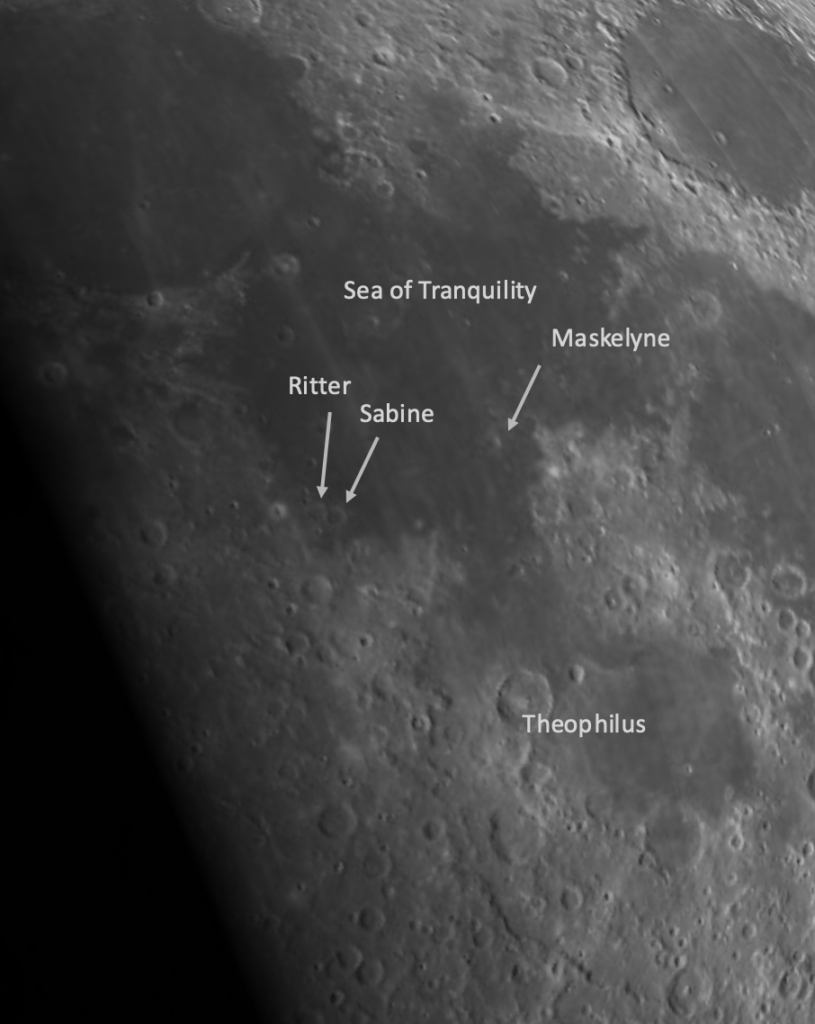

The immortal words of Neil Armstrong upon landing on the Moon serve to get us oriented: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” That’s because the little lunar module Eagle set down, with just a few seconds of fuel remaining, in the southern reaches of the large dark, smooth floor of what’s known as Mare Tranquilitatas, the Sea of Tranquility. The landing site of Apollo 11 lies between the mid-sized craters Maskelyne and Sabine, slightly closer to the latter.

With a telescope, you’re not going to see Neil Armstrong’s “small step for [a] man”, to be sure, or even the first stage of the lunar module left behind by the astronauts. But you can find the general area of the landing, a carefully selected lava plain where the spacecraft could land safely without tipping over on a boulder or off the edge of a crater into oblivion.

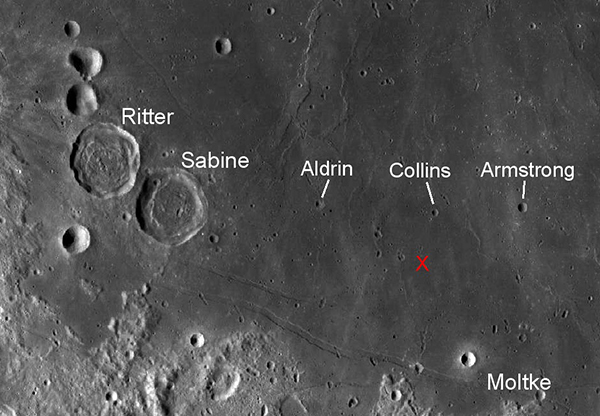

And you can, with the help of a 6″ or larger telescope, see three small pot-shaped craters named for the astronauts Armstrong, (Buzz) Aldrin, and (Michael) Collins by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) after the mission.

The three craters are tiny, just 4.6 km, 3.4 km, and 2.4 km across, respectively, so you may have ‘crater hop’ to locate them. To find your way, your best bet is to find the large crater Theophilus, then look north to find the smaller craters Maskelyne and the side-by-side craters Sabine and Ritter using a moderate magnification of about 100x. Center your field of view on a line between Maskelyne and the two craters Sabine and Ritter about 2/3 of the way to the latter two craters and north of the crater Moltke. Then power up to 200x-250x or more and start looking carefully just east of Ritter and Sabine. Remember that “east” on the Moon is “west” in the direction of our sky.

In rock-steady sky, a good telescope with a 6″ objective will reveal Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins. Keep in mind that Ritter and Sabine are about ten times the diameter of the smallest of the three ‘Apollo 11’ craters. A bigger scope will usually give you a better chance of spotting them, especially on nights of steady seeing when the Moon is near its highest point in the sky. And most importantly, the craters are best seen when the Sun’s light is casting longer shadows to make them stand out. That means observing when the Moon is at first-quarter or a couple of days after, or for an equivalent period just before and at third quarter. When the shadows are less elongated near full Moon, these craters are nearly impossible to find. If you don’t succeed the first time in finding these craters, then try again when the lunar phase is just right. They’re not going anywhere for a long while.

The image below shows you a close-up of the ‘Apollo 11’ craters near the larger craters Sabine and Ritter lined up in a neat row on the southern edge of the Sea of Tranquillity. This is what you’re looking for.

The promise of space travel deeper into the solar system spawned in the 1960s and early 1970s may, so far, have been unrealized. In fact, it’s amazing that no one has set foot on the Moon since 1972. But with a good telescope, steady sky, and a little patience, it’s possible to hover over the surface of the Moon, see this iconic landing sight, and imagine what it was like overcome so many technical and human obstacles to set down for the first time on the surface of this world of ‘magnificent desolation’.

Share This: