The best way for an amateur astronomer to literally expand his or her horizons is to venture to the hemisphere opposite your home, to take in the starry wonders hidden from view by the pesky curvature of our globe. This is especially true for natives of the Northern Hemisphere, because the southern circumpolar sky offers some of the most spectacular sights available to any observer. Fine as the Big Dipper and the Double Cluster may be, they struggle to compete with the Magellanic Clouds and the southernmost parts of the Milky Way.

This is the philosophy that led to my three visits to New Zealand. I’m writing this from the Bay of Islands on the North Island, at 35o south latitude. I’ll share some of my observations in this inaugural edition of my observing column, Eyes on the Deep Sky.

Without a telescope I’d be limited to gawking at these star-spangled skies with only my very portable eyeballs. Fortunately, I also have an airline-portable telescope which has accompanied me on all my visits to Aotearoa, an Astro-Physics Stowaway, a short 92mm apochromatic refractor. A small telescope indeed, but not lacking in quality and versatility.

In the late months of southern-hemisphere summer, the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) in the constellation Tucana sinks a little lower night by night, so I decided to concentrate on this nearby galaxy for my first observations before it gets too low for good viewing. Seen from a dark site like my location at the Bay of Islands, the SMC looks like an amorphous mist three or four degrees across, about half the size of the nearby Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), and it’s less prominent. Lying relatively nearby at about 200,000 light-years, the two Magellanic Clouds are the only external galaxies close enough to permit detailed examination with small telescopes. Both clouds are easy naked eye sights that have no real equivalent in the North. The SMC is also cataloged as NGC 292.

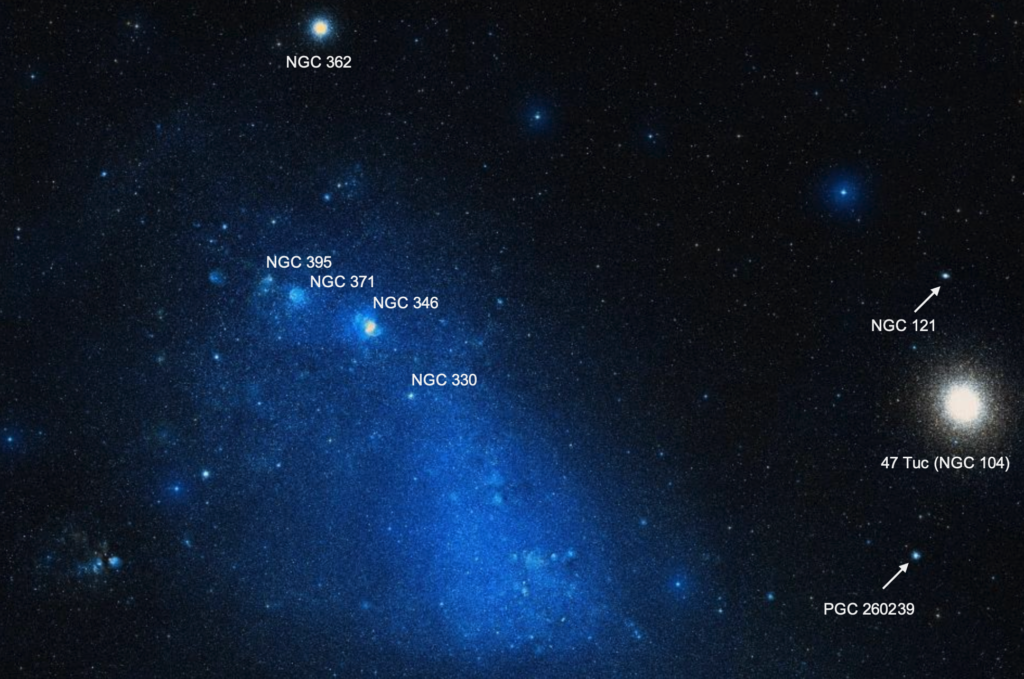

A first glance at the SMC at a low magnification of 27x reveals so many smudges and sprinkles that settling on a few of them is almost bewildering. One good starting point is the globular cluster NGC 362. This relatively little-known cluster is a foreground object, located a scant 28,000 light-years away. Seen from there, the SMC itself would appear only a little bigger and brighter. Overpowered as it is by its flashier neighbor, the globular cluster 47 Tucanae, NGC 362 still competes with any Messier globular cluster available to northern observers. Shining at 6th magnitude, my little telescope at 86X shows it as a smallish, very condensed object, very bright at the core. Its halo, which spans about 10 arc minutes in my eyepiece, is peppered with about twenty faint stars.

A low-powered view of NGC 362 reveals an intriguing field. About a degree and a half south, deep within the glow of the SMC itself, is a conspicuous line of three bright clusters or nebulae. All three look approximately circular at 50x. The brightest member is NGC 346. Described as a nebulous cluster, which fits its visual appearance, this object is associated with the SMC and it span about 100-200 light-years, making it at least four times larger than the Milky Way’s famous Orion Nebula. It has a central, brighter region that is clearly elongated, and shows hints of a more complex structure, but teasing out those exact shapes would take a bigger telescope than mine, or a better observer.

The next object in this line is NGC 371. Another nebulous cluster, it’s not quite as big and bright as NGC 346, but it’s still very distinct. A round glow with a definite border, the telescope also shows a mass of faint stars in this area. Faint as they may appear, seeing individual stars in another galaxy with a small telescope is noteworthy. Of course, given that they are 200,000 light years away, those stars are anything but faint in reality.

The final object in this row is NGC 395, the smallest, faintest, and most irregular of the three. It is nevertheless distinctly visible in this small telescope under good conditions.

If you’re using Sky Safari Pro to navigate these stars, as I was, you’ll find it doesn’t plot 371 or 395 as such. It does show many of the stars that make up these objects, but to show them plotted and labeled by name you have to perform a search for them. This creates visual confusion, as these objects are far more prominent than the tiny clusters which are plotted in this area, and which I never noticed.

A tiny cluster which I did notice lies a little off the line established by the previous three objects, and is of a very different visual character. NGC 330 is listed as an open cluster by Sky Safari, but other sources call it a globular. Based on its appearance in images and through the eyepiece, I think its identification as a globular is more likely. It spans only about one arc minute in my telescope, and consists mainly of a tiny, elongated bright core which may consist of as few as two brighter stars. I couldn’t quite make out the true nature of this minute glow with my small aperture. A few nearby faint stars may be associated with this cluster, but that’s about all there is to this remote object.

Now we move on to the primary superstar of this whole area of the sky, the magnificent globular cluster 47 Tucanae. Easily visible to the naked eye as a 4th magnitude star lying just west of the SMC, this cluster has no rival in the north, and puts up a good fight against Omega Centauri for the title of Greatest Globular Cluster. Both objects received star designations before their true, non-stellar nature was discovered. 47 Tuc is more formally known as NGC 104.

Seen in my itty-bitty refractor, 47 Tuc utterly dominates its field at 50x, or indeed at any other power. It’s strongly concentrated toward the center, which is a solid blaze of creamy light. Its expansive halo, which appears at least thirty arc minutes across, is powdered with a hundred or so tiny, perfect star-flecks, though Tui, my friend and host here in New Zealand, could not make out any of the individual stars. This cluster lies about 13,000 light-years away, making it one of the nearest globulars, which partially accounts for its grandeur for those lucky enough to see it.

While I was in the neighborhood, I decided to check out a pair of nearby objects which are hugely overshadowed by its justly famous neighbor. The first is NGC 121, another globular cluster, but sharing the same apparent relationship to 47 Tuc as a flea does to a dog. It’s 200,000 light-years away, and associated with the SMC! That means it’s fifteen times farther away than 47 Tuc, which explains why it looks so small and inconspicuous in my refractor. I estimated its brightness as magnitude 11, which is backed up by other sources. It’s just a tiny glimmer, maybe one arc minute across, lurking inconspicuously and rarely noticed.

Finally, I decided to try for something I didn’t expect to see at all. Lying roughly opposite of 47 Tuc from NGC 121, PGC 260239 is a little-known galaxy, easily located due to its involvement with a short line of three stars of magnitudes 10-12. These stars were obvious in my telescope at 50x, and the galaxy itself was surprisingly apparent, a fair-sized if vague elliptical glow with some central condensation. Sky Safari calls it magnitude 13, but I think it must be brighter than that to be visible in my telescope, especially given its substantial angular size.

After ferreting out a few deep sky objects ranging from the glaringly obvious to the faint and obscure, it’s refreshing to lean back from the eyepiece and take in the stunning sights of the looming Large Magellanic Cloud, and the swath of brilliant Milky Way that holds so many wonderful and legendary objects. More on some of those next month.

Share This: