Unlike galaxies and star clusters and even emission nebulae, the class of objects known as planetary nebulae exist on a scale of space and time that’s comprehensible, relevant, and compelling to most humans.

Comprehensible because these tenuous exhalations of dying stars are roughly the size of a solar system, which means light can pass from one end of the nebula to the other in just a few hours, and even our current spacecraft could cross some of these nebulae in a matter of years.

Relevant because our own Sun will expire after creating its own planetary nebula in a few billion years when our star’s inner core boils off its outer layers in an intermittent nuclear frenzy.

And compelling because as you observe these objects with your telescope, you may be witnessing the death of other solar systems which once harbored intelligent civilizations that long ago passed into oblivion, or perhaps learned to travel elsewhere in the galaxy before it was too late. Amateur astronomy is, after all, a pastime of the imagination.

Most stars will eventually become planetary nebulae, if just for a few tens of thousands of years out of their billion-year life spans. About 3,000 planetary nebulae exist in our galaxy, and perhaps a hundred are visible to determined backyard stargazers with a small telescope. The “showpiece” planetaries like the Ring, the Blue Snowball, and the Dumbbell Nebulae are favorite targets of even beginning stargazers. Not much further down the list of accessible planetaries is the famous Cat’s Eye Nebula (NGC 6543). It’s one of the newest such nebulae, just a thousand years old, and one of the easiest to see because of its high surface brightness.

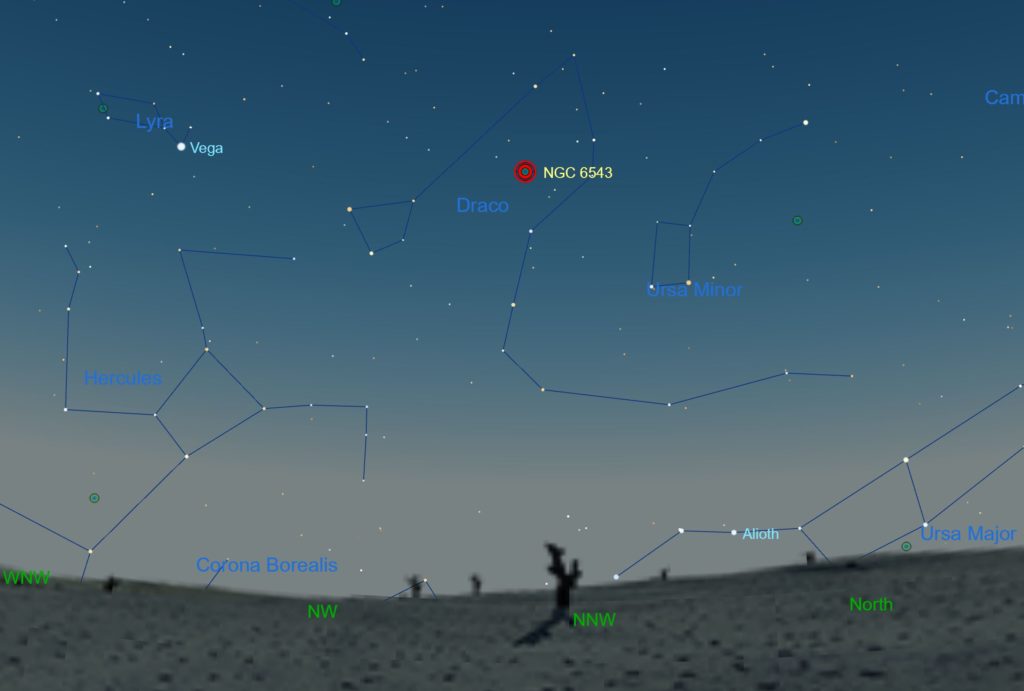

The Cat’s Eye is the only planetary nebula among the winding stars of the constellation Draco which lies between the Big and Little Dippers. The 8th-magnitude nebula is located about halfway between the stars delta (δ) and zeta (ζ) Draconis. For northern stargazers, the nebula (and Draco) are visible before midnight from May through November, more or less. These stars are not visible from the deep-southern hemisphere.

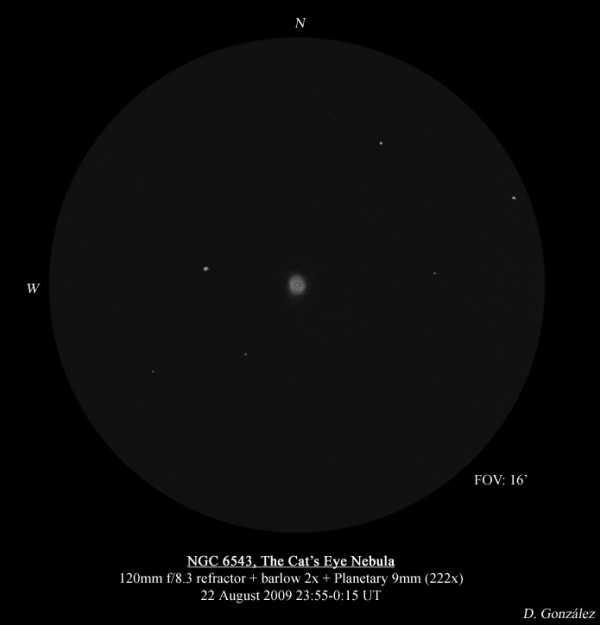

Unlike larger planetaries like the Helix Nebula, the Cat’s Eye is tiny, some 16″ across, and has a relatively high surface brightness which makes it easier to see in light-polluted skies. With a 4-inch or larger telescope at 30x to 40x, you’ll just be able to discern the nebula from the surrounding stars. It may look slightly fuzzy, with perhaps a greenish or turquoise color. The trick is distinguishing it from a star. That’s where more magnification will help, at least 100x and preferably more, to give it some size. If you thread a nebula (or light pollution) filter into your eyepiece, it will also help increase the contrast of the nebula compared to the stars and the background sky.

The central star of NGC 6543, the old star that’s casting off the nebula itself, is fairly bright and most telescopes reveal it easily with modest magnification. At 150x or more, the nebula shows some texture, including somewhat darker inner region and a brighter ring around the outside. The shape is slightly oval, and the color is quite pleasing compared to the whitish stars in the background. Like most small planetary nebulae, the Cat’s Eye responds well to high magnification if the sky is steady. In larger telescopes at 200x or more, you may see a glimmer of the intricate shape that lends the nebula its name.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, many astronomers thought planetary nebulae were patches of unresolved stars, which was not an unreasonable hypothesis. After all, as telescopes improved, once-unresolved star clusters were revealed to be tightly-packed groups of individual stars. Others thought nebulae were made of a shining “celestial fluid”. The debate was solved in 1864 by William Huggins, a self-taught British amateur astronomer and wealthy silk merchant who sold his business at age 30 to concentrate on astronomy full time. Huggins was the first to attach a laboratory spectroscope to a telescope to try to figure out the composition of celestial objects. When he turned a spectroscope to the Cat’s Eye, he found its spectrum was completely different from any star. He attributed the strange spectrum to an undiscovered element he called “nebulium”. Decades later, spectroscopists determined “nebulium” was really a form of ionized oxygen that exists only in the rarified vacuum of space. This type of oxygen ion is called OIII (“oh-three”). Huggins subsequent studies of stars and nebulae determined that celestial objects were made of many of the same atoms as the Earth. “A common chemistry exists through the galaxy”, he wrote.

While the Cat’s Eye is modest in a backyard telescope, it is dazzling in long-exposure photographs. A splendid image from the Hubble Telescope made this nebula famous nearly two decades ago. Here’s an updated image from Hubble. The twists and turns in the nebula are a matter of current study, but they are likely the result of the complex interplay of a companion star with the dying star, intermittent energy production in the dying star, and stellar magnetic fields coupled with stellar rotation.

The size and expansion rate of the Cat’s Eye suggest the nebula is just 1,000 years old. The central star will continue to expand for another 10,000 years, give or take, just a tiny fraction of its total lifespan, until the central star runs out of atmosphere. The ejected gas and sooty dust from the outer and inner parts of the star will quickly cool and drift freely in interstellar space for millions of years. Some of this material may one day coalesce in dense clouds that will collapse and form new star systems. A planetary nebula is but one instance of the complex ecology of the Milky Way as old stars recycle themselves into new stars and planetary systems.

(Editor’s Note: The Cat’s Eye Nebula is one of more than 400 celestial objects you can see for yourself with the help of What to See in a Small Telescope, a series of online courses exclusively available to subscribers of CosmicPursuits.com).

Share This: