One hundred years ago, the universe was quite small, or at least people thought it was. Not so small that you could put it in your pocket, but limited to the Milky Way Galaxy only, which was thought to be about 30,000 light-years across, or maybe a little more.

Beyond that, if there was anything at all, it was simply an empty void.

That’s because no one was sure what the so-called “spiral nebulae” really were. They were dotted across the sky, often in clusters, though they were scarce along the band of the Milky Way. When astrophysicists analyzed their light spectroscopically, those spectra showed star-like characteristics, but no telescope on Earth could reveal individual stars, either visually or photographically. They remained mysterious, and often beautiful, whirlpools of light.

So although some astronomers suspected these spirals were in fact remote “island universes”, more of them believed they were closer, lesser things, perhaps infant solar systems in the process of forming.

Slightly less than one hundred years ago, these questions were resolved, along with the galaxies themselves, and the size of the known universe expanded one hundred thousand times or more, almost overnight.

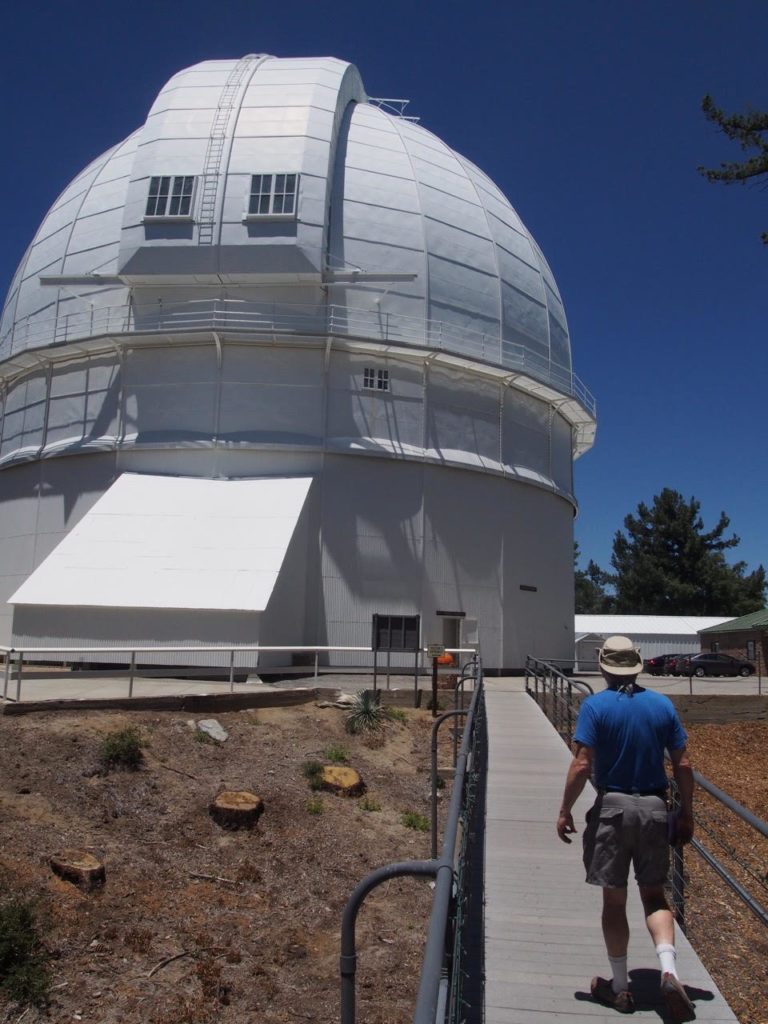

And that’s where the Mount Wilson Observatory in California comes in. Its namesake mountain sits at the edge of the vast carpet of artificial lights known as the Los Angeles Basin, looking down on it from 5700 feet above the not-so-distant Pacific Ocean. Today that massive light pollution renders the observatory useless for most kinds of nighttime astronomical research. In its heyday in the early 20th Century, it was the world’s greatest center of astronomical discovery. It was one of the first observatories ever to be sited on a mountaintop for performance, not in or near a city for convenience. Back then it could ignore the feeble lights of Los Angeles and the other small communities flickering below.

Mount Wilson was one of the many brainchildren of George Ellery Hale, one of the most important figures in the history of astronomy. Born in 1868 as the son of a Chicago elevator mogul, Hale spent his youth tinkering with scientific instruments, eventually acquiring a series of ever-larger telescopes, thanks to his solicitous and wealthy father. These did not satisfy him for long. Going on to become a noted solar astronomer, astrophysicist, professor, and inventor of the spectroheliograph, Hale eventually made use of his talent for cozening wealthy industrialists and institutions, extracting from them the funds needed to build a series of major observatories, each of which contained what was, for a while, the largest telescope in the world.

The first of these was the Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin, whose 40-inch refracting telescope, biggest in the world, demonstrated that refractor development had reached its zenith, and that it was time to look to bigger reflectors if astronomy was to be advanced. The lakeshore setting of Yerkes demonstrated that low-altitude, cloudy Eastern locations were not ideal for astronomy.

Hale thus set his eye on Mount Wilson, then a dark site, and one that offered reliably good seeing, because there was nothing between the mountaintop and the sea to disturb the calm flow of air over the telescopes. At first known as the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory due to its first two functioning instruments being dedicated solar telescopes, Mount Wilson saw first light of its first major astronomical telescope, the 60-inch, in 1908.

I visited this storied observatory some 110 years later, in the summer of 2018, when I was offered a private tour of the observatory by Nik Arkimovich, a professional photographer and one of the volunteer tour guides and telescope operators at Mount Wilson. With my uncle Bob Bergeron and his wife Georgianna along for the ride, we drove up into the San Gabriel Mountains on a nice sunny day. The observatory occupies a ridge which offers spectacular yet very different views on either side. To the east are the wild peaks and valleys of the San Gabriels. To the west stretches the coastal plain occupied by ten million or so human beings who can, on a clear day, look up into the mountains and see the domes and towers of the observatory. We arrived on a day that was not so clear down in the city, hazy enough to prevent any glimpse of the Pacific.

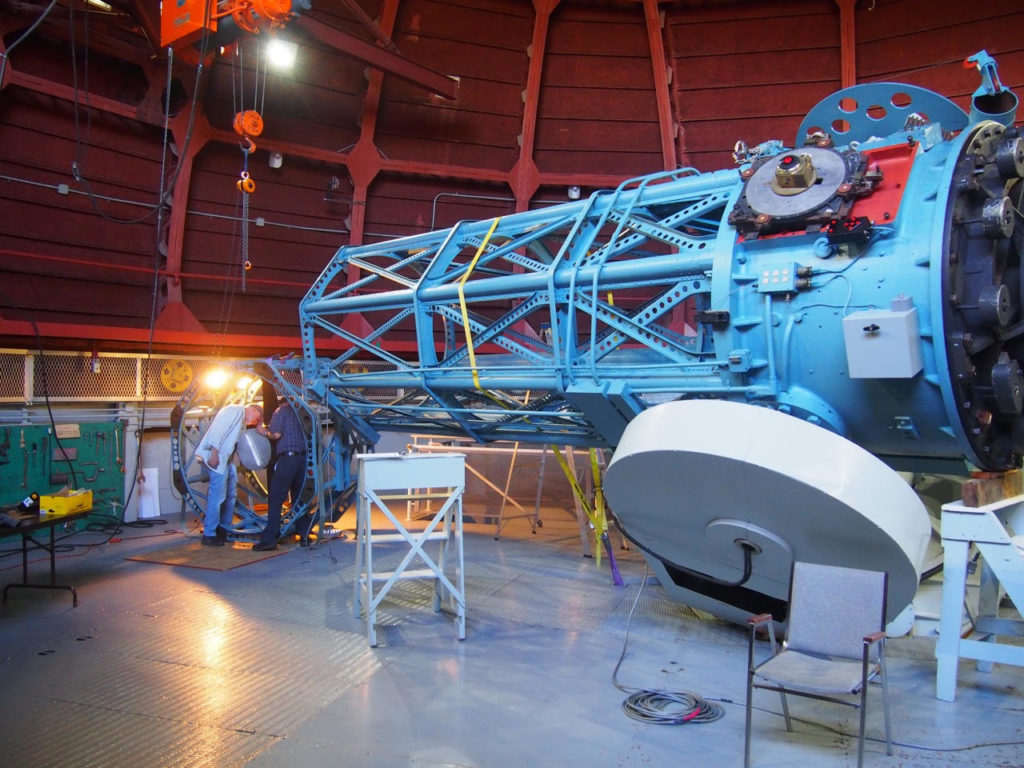

Nik first led us into the dome of the 60-inch. Like so many Hale telescopes, this was the biggest functioning telescope in the world when it went into service. It was also a prototype for many large research telescopes built thereafter. Its equatorial fork mount could reach the entire sky, and track with the accuracy required for long-exposure astrophotography and spectroscopy. Its truss-tube construction resulted in a lighter, stronger telescope with better ventilation to avoid image-degrading currents of warm air. Its versatile optical system could be configured into Newtonian, Cassegrain, and coudé arrangements to facilitate various instruments and purposes.

Today this venerable instrument can be rented for viewing by groups or individuals. Although compromised by the light pollution coming from the megacity down the hill, the telescope is still well suited to providing spectacular views of planets and small, bright deep sky objects such as globular clusters and planetary nebulae.

In the basement of the 60-inch dome is a bank of vintage wooden lockers, each still assigned to some long-dead astronomer. One of them is Edwin Hubble. When I wondered what Hubble might have left in his locker (perhaps a sandwich or some other snack), Nik invited me to find out. Opening the door, I was confronted with Hubble’s stern face staring out at me, annoyed with my impertinence at investigating his personal belongings.

The Cambridge-educated Hubble had a reputation for being a bit imperious, perhaps even pretentious. He always struck me as the perfect example of an impressive astronomer: profoundly serious, physically imposing, unlikely to shy away from a fight. He was also very much at the right place at the right time.

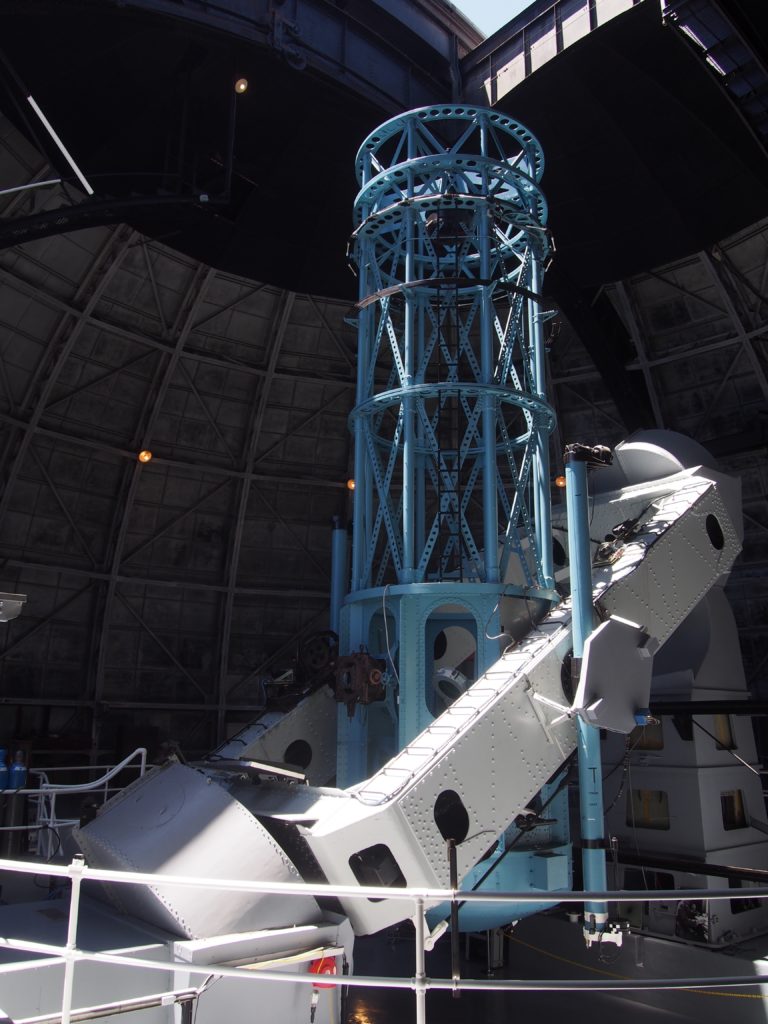

Nik then led us into the dome of the 100-inch Hooker telescope (named for John D. Hooker, the Los Angeles hardware magnate who provided the initial funding for the telescope), which functioned as the world’s biggest telescope from 1917 to 1949 until the 200″ Hale telescope at Palomar Mountain saw first light. It is also one of the most historically and scientifically important telescopes ever built.

Hubble arrived at Mount Wilson shortly after the telescope was completed. Assisted by the former mule driver Milton Humason, who parlayed his work delivering components to Mount Wilson into eventually becoming a full-fledged staff observer, he revolutionized our view of the universe, its size, and our place within it, by careful use of the immense new telescope.

Although small by current standards, the Hooker, with its 500-inch focal length, is still very impressive, occupying a dome big enough to contain a modern 19-meter reflector. Its elaborate truss tube, painted a bright cheery blue, looks like something Captain Nemo might have constructed, if his interests had led him in that direction. Present in the dome is the original control console, a piece of fine wooden furniture equipped with electric lighting and a pair of telescopes for reading the setting circles on the main instrument.

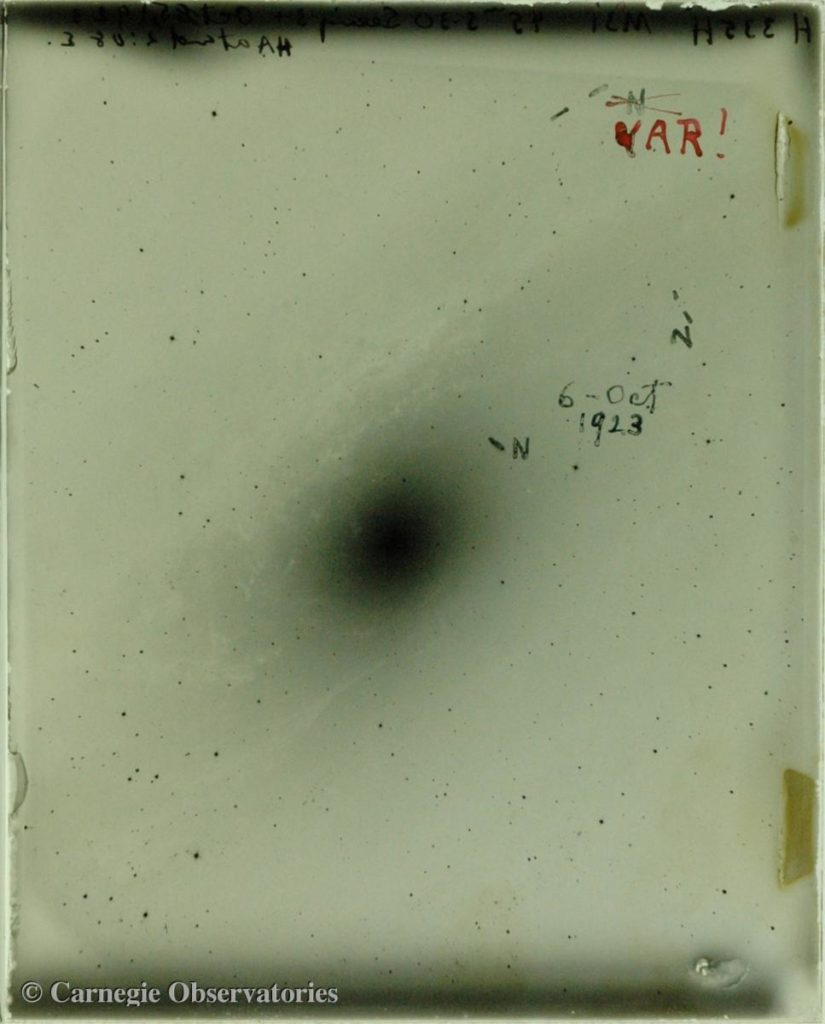

The Hooker was the first telescope big enough to resolve a few nearby galaxies into individual stars, and that made all the difference. Among the stars Hubble detected on his photographic plates were Cepheid variables, a major key to determining the scale of the universe. The Cepheids within our own galaxy had been found to have a very useful property. Their brightness is directly correlated to their period of variability. This means that if you measure the period of a Cepheid, you then know its overall luminosity. Measuring its apparent brightness, you can then calculate how far away it must be. This makes the Cepheids extremely valuable distance indicators. This class of stars is named after Delta Cephei, a naked eye star and the first star of its kind to be identified.

Hubble photographed and measured Cepheid variables in M31, then known as the “Andromeda Nebula”, the brightest and most prominent “spiral nebula” visible from Mount Wilson. Hubble determined from this that the Andromeda spiral lay about 600,000 light-years away, well outside the limits of our Milky Way. It was therefore a separate galaxy in its own right, or an “island universe” as they were often called back then.

Hubble’s initial figure of 600,000 light-years was off by a factor of about four, but it showed the way. He was able to detect Cepheids in a few other nearby galaxies as well, establishing once and for all the magnitude of cosmic distances, extending millions, and ultimately billions, of light-years in every direction.

Later, Hubble and Humason further contributed to revolutionizing astronomy by using the Hooker telescope to determine that the universe appears to be expanding, but that’s another story.

Our final stop on the tour was the Monastery, a dormitory for astronomers visiting the observatory. We entered the dining room, where the observer assigned to the 100-inch (often Hubble) presided over dinners, ringing a bell to signal the changing of each course. We visited the library, its walls lined with books too old to be taken down and opened. There my aunt and uncle sat in a chair occupied by Albert Einstein during his visit, hoping to absorb some of his intelligence through psychic osmosis.

I recommend a visit to Mount Wilson Observatory to anyone who gets the chance. It would be an especially welcome oasis for anyone living in the vast sprawl of humanity so far below. The tree-filled grounds have a peaceful air that befits the history and the lofty purpose of the institution. Today the observatory is operated by the Mount Wilson Institute (MWI), a private group that sustains the observatory through tourist visits, concerts in the 100-inch dome, donations, and telescope rental fees. Besides the two great reflectors, the grounds also include various solar telescopes and the CHARA interferometric array, which is still actively used for research and is capable of extremely high image resolution.

Recently the director of MWI, Samuel Hale, grandson of observatory founder George Ellery Hale, visited the annual Stellafane astronomy convention in Vermont. There he spoke on the great historical importance of the observatory, and the need to maintain and preserve it. It is indeed, in my opinion, the most historically significant observatory in the world, the place where modern cosmology got its start, and the place where the universe truly opened up before our eyes.

Share This: