The planet Mars is coy. It spends most of its time as a relatively inconspicuous star-like object, only moderately bright, drifting barely noticed though the sky, little seen, or sometimes hiding behind the Sun.

Once every two years it grows bolder. It decides to put on a show. But even then, it’s sneaky about it, gathering its glory in the late hours of the night, seen mainly by dedicated astronomers, those who know what to expect and where to look.

And then, at the apex of its splendor, it rises at sunset, blazing across the sky all night for a few brief weeks, revealing itself in a level of detail far beyond what it will normally display.

Of course, this description of Martian behavior is pure anthropocentric nonsense. As far as Mars is concerned, it’s just wheeling around in its orbit as usual, and if that little blue light closer to the Sun cruises by once each (Martian) year or so, it barely notices. Though the planet has noticed that lately, whenever the blue light is a bit ahead relative to itself, a little later one or two tiny metal fleas may descend onto its surface, or perhaps settle into orbit around itself.

This is the situation we are experiencing now. The passage of Earth between the Sun and Mars (or any other outer planet) is called opposition. In the case of Mars, it occurs at an average interval of two (Earth) years and fifty days, as the speedier Earth catches up to Mars and passes it in its orbit. The distance between the two planets varies between oppositions, because neither has an orbit that is exactly circular. At a good opposition, like in 2003 and 2018, the planet is less than 36 million miles away, about 150 times the distance to the Moon. At a poor opposition, the planet is 61 million miles away and proportionately smaller.

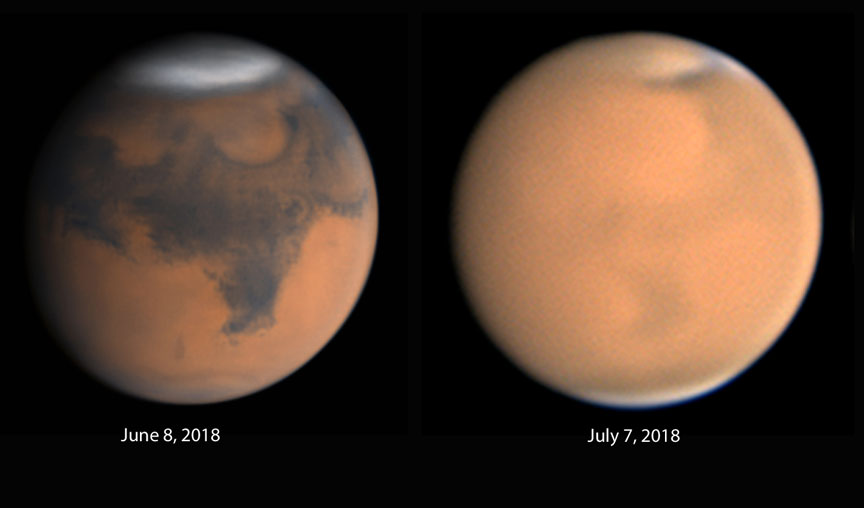

Even when Mars does decide to show off, it may still become shy at the last minute and throw a veil over itself. When Mars makes an unusually close approach to the Sun, the increased warmth can cause planet-wide dust storms that obscure or even entirely conceal the dark markings that amateur astronomers try to pick out with their telescopes. Such dust storms make the planet appear blander than any observer would wish.

Opposition and closest approach must be the ideal time to send spacecraft, and maybe even astronauts, to Mars, right? Well, no. Chemical rockets are too weak to overcome the velocity difference between the two planets and send much of anything there on a direct path. Instead we must wait for the planets to align in such a way as to permit a low-energy Mars Transfer Orbit. This allows a spacecraft to sweep out a leisurely path to Mars that takes ten months to complete. That time doesn’t mean much to a robot spacecraft, but it’s a major obstacle to any manned exploration of Mars.

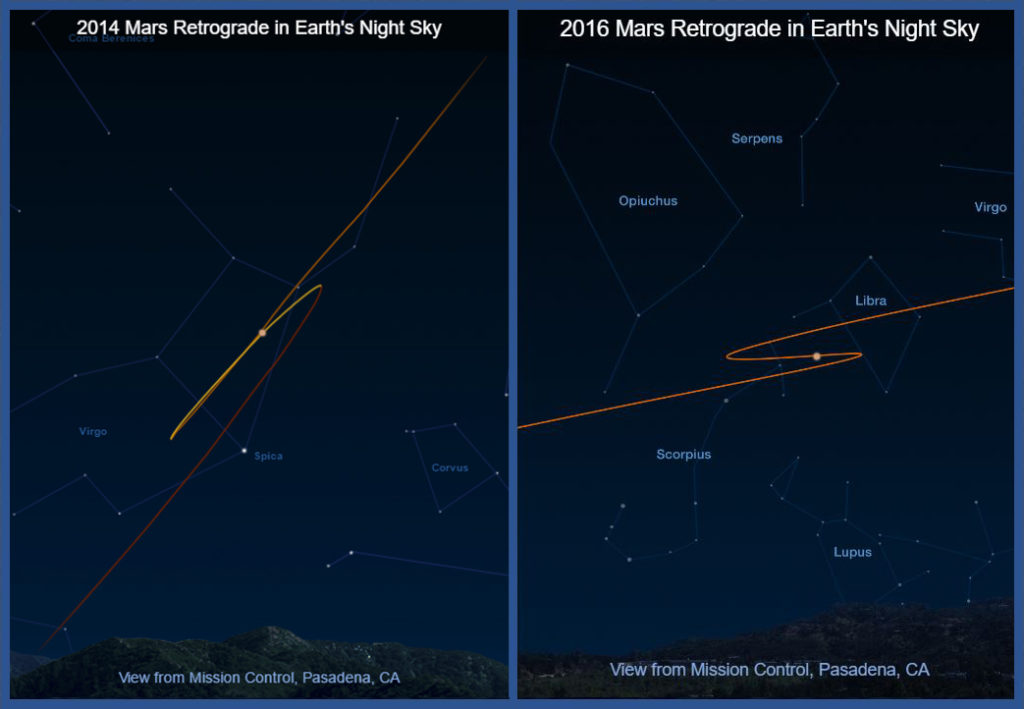

Now, here’s your chance to play Junior Ancient Scientist. For two or three months before and after opposition, go out every night, note where Mars is relative to the background stars, and plot the position of the planet on your map. Connect the dots, and you will notice a peculiar thing. Ordinarily, Mars and the other outer planets appear to slide among the stars from west to east as they move in their orbits. But, if you begin recording the position of Mars in the weeks before and after opposition, you will find that it’s moving backwards!

We call this retrograde motion, and the explanation is simple enough. During opposition, Earth is catching up with, and then passing, Mars (or any of the other outer planets) in its orbit. If you pass anything, such as a car in the slow lane as you’re driving, it appears to be moving backwards from your point of view. If you had begun plotting the location of Mars, you would have found that its path described a loop, not a simple back and forth motion, because the two worlds do not orbit the Sun on exactly the same plane.

This behavior doesn’t seem too puzzling now, but to the ancients it was deeply mysterious. It wasn’t enough that the planets were the only “stars” that moved among the other, “fixed” stars, but sometimes they had to stop, back up, and then continue on again. No wonder they seemed supernatural. No wonder they were called “wandering stars”.

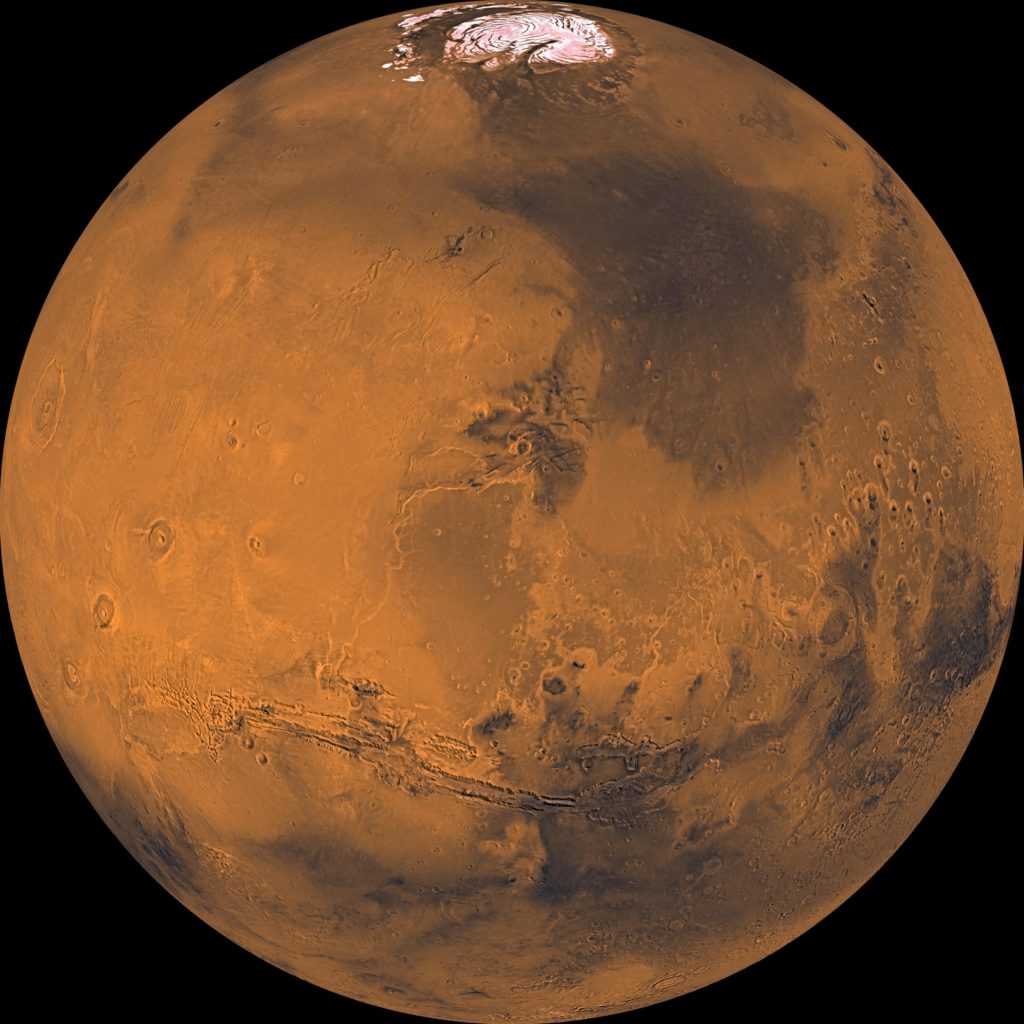

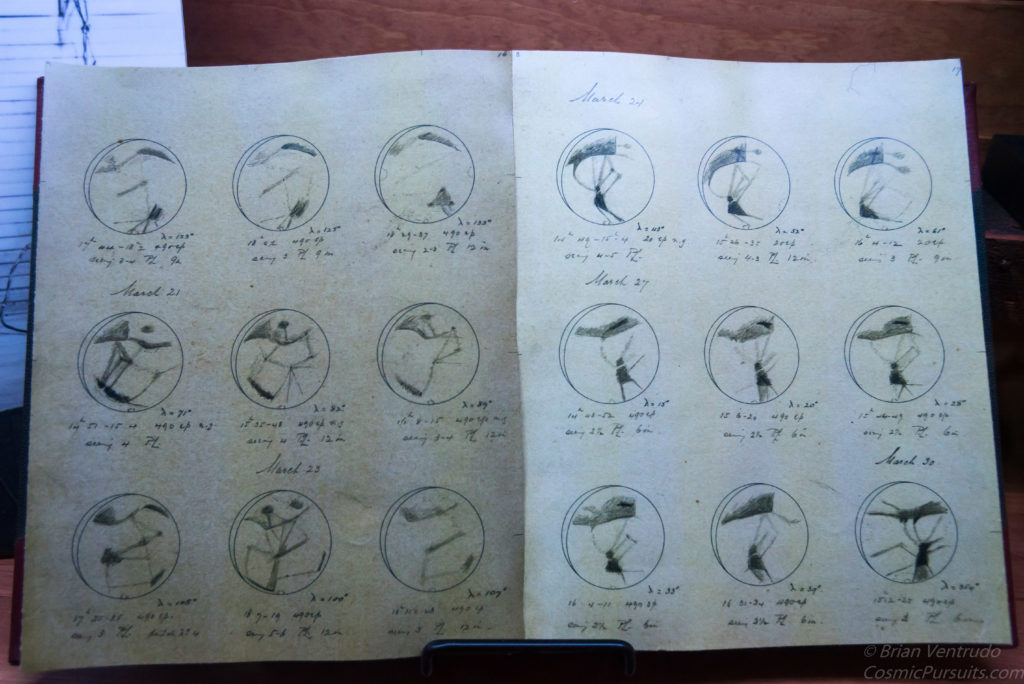

Opposition, normally, is the best time to observe Mars through a telescope. For many years, all we knew about the physical nature of Mars was learned by peering through telescopes, mostly during those fleeting oppositions. Observers saw white polar caps of ice, and correctly interpreted them as such, though it took a while to realize the planet is so cold they are mostly composed of frozen carbon dioxide. They saw persistent dark markings, convinced themselves they changed color seasonally and were sometimes green, and erroneously concluded they were patches of some primitive vegetation. A few of those observers (Giovanni Schiaparelli most notably) thought they saw fine, narrow lines crisscrossing the planet, and fewer still (Percival Lowell) imagined they represented artificial canals.

In other words, we knew little about the true nature of Mars until our robot spacecraft began to visit it in the 1960s. Amateur astronomers can still look at the planet, still see those same dark markings and polar caps, and even try to make out non-existent canals, exactly as those 19th-century astronomers used to do. Many of today’s amateurs have better telescopes in their back yards than most of those old-time professionals had in their domes. Advanced imagers can capture the planet in even greater detail than what the eye can discern.

What is the relevance of Mars to the human race? In my opinion, it’s mostly as a repository for the imagination. We can no longer dream of exotic Martian civilizations using their canals to stave off the desiccation of their dying world. Nor can we speculate about mosses and lichens that change color with the change in the Martian seasons, but we can still wonder about whether that cold, dry little world once harbored life that we would recognize. We can send robots to look for whatever clues and remnants such life might have left. We can dream of sending human explorers to that enticing little planet, though I believe that will have to wait for the advent of technology well in advance of anything we now possess, at least if we wish to retrieve our astronauts in good condition.

And we can stare at Mars with our telescopes, putting ourselves in the place of those old astronomers who tried to determine the nature of that distant world by peering at a small, wavering image in their eyepieces. Mars may have lost its old mystery and romance, but if gaining knowledge is our goal, we are now much better off.

Or we can look back even farther in time. Even if you don’t have a telescope, look for Mars around the time of opposition, when it’s highest at midnight, a fiery orangish light. You can’t miss it. Try to imagine what an enigma it must have been to ancient peoples, this flareup of something usually so inconspicuous. What would you have made of it?

Share This: