More than most planets, Mars has captured the public imagination as a place of mystery, a target of exploration, and possibly the only other place in the solar system that may have once harbored life. The planet figured prominently in science fiction, from the early tales of E.R. Burroughs and H.G. Wells to the latest work of Andy Weir. And Mars is now on the radar of hands-on visionaries like Elon Musk who plan to colonize the planet in the coming decades. The popular fascination with Mars began more than a century ago in the fertile imagination of Percival Lowell, a wealthy and intellectually restless astronomer who speculated about intelligent life on Mars and left a lasting legacy for astronomy.

Lowell came from an old, wealthy, and enterprising Boston family that first settled the Cape Ann peninsula of Massachusetts in 1639. His brother Abbot was president of Harvard University for 24 years, and his sister Amy was a well-known poet. Percival himself was a Harvard grad, majoring in mathematics. He developed an interest in astronomy as a student and delivered a graduation address on the “nebular hypothesis” of solar system formation.

But that was it for astronomy for young Percy, or so it seemed. After Harvard, Lowell traveled a bit, then managed a cotton gin for six years. With some real-world experience under his belt, and with his trademark intellectual ambition, he traveled to Japan, studied its culture and language, and came to serve as a counselor for a Korean diplomatic mission to the U.S. He returned to Japan and Korea on and off for another decade, learned both languages, and wrote four academic books about the culture and history of Japan and Korea, including “The Soul of the Far East” in 1888 and “Chosou—the land of Morning Calm—A Sketch of Korea” in 1886. He returned to the U.S. in 1893, age 38, looking for his next challenge.

He found it, once again, in astronomy. Inspired by the florid writings of Camille Flammarion and the observations by Giovanni Schiaparelli of Martian canali (which translates from Italian as channels, not canals), Lowell became convinced Mars was inhabited by an intelligent civilization that built structures visible in a large telescope from Earth.

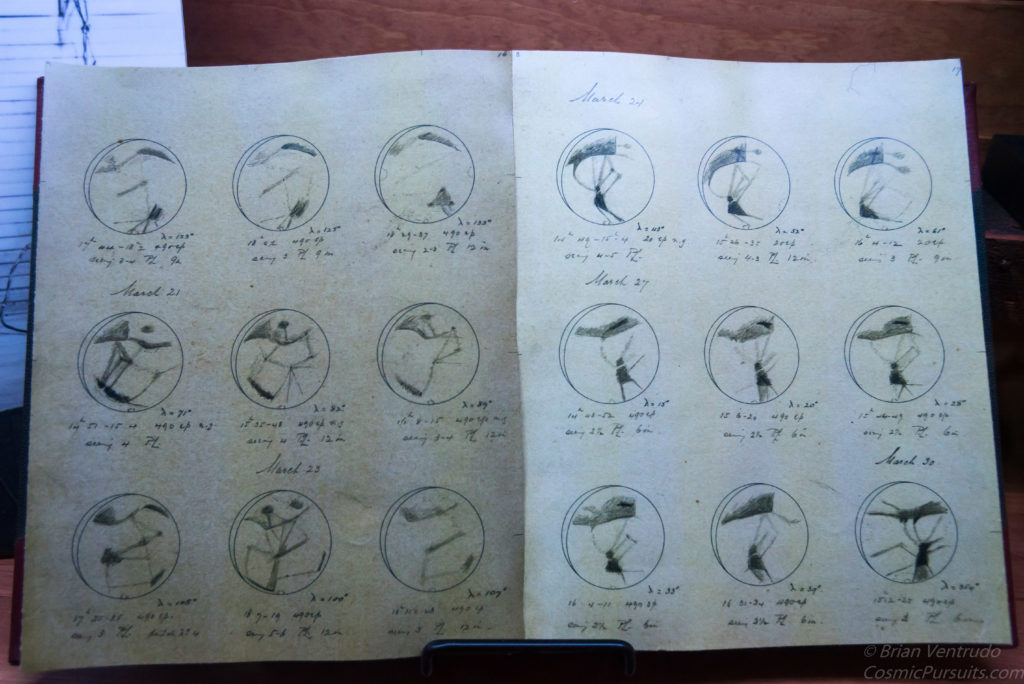

In 1894, Lowell used his part of his family fortune to quickly build an observatory near Flagstaff in the clear, dry, and dark Arizona sky. It was the first major observatory located at a high altitude and away from the increasingly polluted skies of major university towns where electric lights were starting to diminish the views of the night sky. At his nascent facility, Lowell set up two borrowed refracting telescopes and set to work sketching the surface features of Mars, and he continued sketching and making measurements of Mars for more than 15 years. His observatory eventually housed an impressive 24-inch refractor made by Alvan Clark. The telescope remains in use at Lowell observatory to this day.

Not long after his first observations in 1894, Lowell loudly announced his discovery of canals and oases on Mars, which he believed were created by the inhabitants of the Red Planet. The public was captivated. Lowell became world famous. And the idea of life on Mars remained in the public consciousness for decades.

Professional astronomers had a different reaction. Many were appalled at Lowell’s thirst for publicity. Some believed he jumped the gun to announce life on Mars without more careful study and analysis. No other astronomers could see canals on Mars, including the eagle-eyed E. E. Barnard with the larger 36-inch telescope at Lick Observatory in California. And spectroscopic studies showed the Martian atmosphere was very likely unable to support life, at least as we understand it on Earth.

Many began to believe (correctly, it turns out) that the canals were an optical illusion. Skepticism about the canals increased amongst astronomers over the 20th century. Though it was not until Mariner 4’s flyby in 1965 that the existence of canals was disproved completely.

If Lowell was troubled by the scorn and derision of the astronomical establishment, he didn’t let it show. He remained at his telescope for the rest of his life, making drawings of Mars, as well as patiently sketching an early map of Venus. Though again, what he saw on Venus was uncertain since we know now Venus reveals no surface features in visible light.

Lowell also predicted a ninth planet– which he called Planet X– based on oddities in the orbits of Uranus and Neptune. He searched for Planet X himself until his death in 1916 at the age of 61. The observatory’s staff continued the search until 1930, when Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto at Lowell Observatory. Though it turns out Pluto was too small to be Planet X, and the whole issue disappeared when, much later, accurate determination of the mass of Neptune showed the outer planets moved as expected.

So Lowell was wrong on Mars. He was wrong on Venus. He was wrong on Planet X.

Was he a failure?

He was not. Though he irritated his professional contemporaries and made few original scientific discoveries, Lowell left the legacy of a world-class observatory which still contributes to the advancement of human knowledge. And he stimulated public imagination for planetary exploration more than anyone else in his time. Among his indirect contributions to astronomy was his somewhat reluctant decision to hire a young Indiana astronomer named Vesto Slipher for a short-term assignment. Slipher, who remained at the observatory for 53 years, made major discoveries about the rotation and recession speeds of spiral galaxies. His observations were the first glimmer of understanding that the universe is expanding, and that it all began billions of years ago in a single sudden expansion called the ‘Big Bang’.

Today, Lowell’s Observatory is a U.S. National Historic Landmark. His mausoleum stands on Mars Hill near the observatory, overlooking Flagstaff and historic U.S. Highway 66 that passes through the city. The observatory operates as an astronomy outreach and research center under private funding. And visitors to the observatory can explore the grounds by day and, on clear nights, look through the grand 24-inch Clark when the telescope opens to the public.

Share This: